A year after the closure of the prison on St Nicholas Island in 1685 Charles II died. Although he had produced numerous sons and daughters none were born to his wife so his brother James became James II of England and VIII of Scotland. Unfortunately James had one major fault as far as the British Protestant Parliament was concerned, he was a Catholic. It was still not illegal for a Catholic to become monarch but all senior British Government and Military positions had to be Protestant. Before his death Charles had insisted James’s daughters, Mary and Anne were bought up as Protestants to try and ensure the succession of the House of Stuart. James was therefore tolerated for the sake of a peaceful succession as long as he would be followed by his Protestant daughters. However something of a crisis occurred when James’s second wife Mary had a son, another James in 1688 who was to be bought up a Catholic. Mary the eldest daughter had in the traditional inter-breeding of the times married her cousin William of Orange, a staunch Protestant from the Spanish Netherlands. To prevent the Catholic succession of James II son James in early 1689 a number of nobles invited William and Mary to take the Throne. William happily accepted and in what became known as the Glorious Revolution he came over with a significant army and was unopposed as James realising he had little support fled for France. To complete the circle Parliament declared James had abdicated and therefore Mary and William were the rightful rulers and for good measure to prevent James II son James claiming the Throne passed a bill preventing any Roman Catholic becoming monarch. This was readily received royal assent from the decidedly Protestant Mary and William.

Trade and Empire were now becoming key for Britain to be economically successful. This required a strong Navy to protect Britain from invasion, project British forces overseas to enlarge and protect the Empire but also to protect the merchant fleet which would be vital for the country’s finances. With Louis XIV of France already wanting to expand his Empire in Europe and abroad there was a fear that Louis would try to interfere in Britain and reinstall James on the Throne as a Catholic vassal of the French Throne. William on taking the throne immediately realised a successful Navy needed a second naval dockyard in the South West, partly so he could disperse his naval assets between the second port and Portsmouth but also as access to the Empire was via the west.

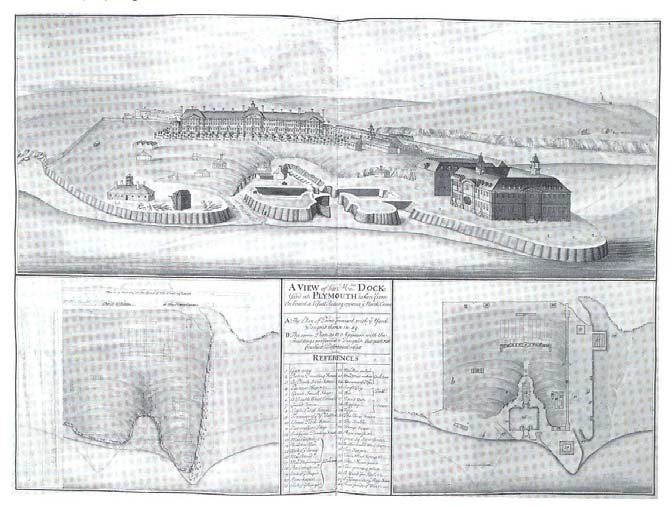

He started a survey of the West Country which finally identified Devonport over the Cattewater as the new Naval Dockyard. The Cattewater was found to be too exposed and Devonport more easily defended. This was partly down to St Nicholas Island being a strong point in the Sound and the longer entrance down the Hamoaze could hold more artillery batteries. The channel to Mount Edgcomb was sufficiently shallow that all attacking ships would have to pass between Mount Batten and the Island then the Citadel and the Island before entering the Hamoaze. The 9 Years War with France had also began in 1688 with Britain taking the opportunity of allying with a number of continental countries to counter the French threat. The Island still had a number of batteries all around the Island and the cannon would still have had a limited range of around 600 metres, roughly the distance between the Island and the Hoe. Each battery would have consisted of a number of firing points with cannon on them. Whilst most batteries would be there to attack enemy ships some batteries would have smaller cannon to ward off attacks on the Island itself by enemy soldiers.

A report of the time stated the following cannon were delivered to the Island in 1690 14 x 42 pounder, 17 x 18 pounder (Culverin), 13 x 9 pounder (demi-culverin), 4 x 5 ½ pounder (saker), 6 x 4 pounder (minion), 1 x 3 pounder (falcon) guns all with supporting gunpowder and shot. The reference to pounder refers to the weight of iron ball the cannon fired. Essentially the larger poundage, the greater amount of powder was required but the cannon had a shorter range. The smallest cannons, the minion and falcon would have been used for Island defence against ground forces if they tried to take the Island. Interestingly there was a direct threat to Plymouth from the French in 1690 and it’s quite likely these cannon were delivered to meet that threat. Vice-Admiral Killigrew wrote in a letter “Having account that the French are at Tor Bay, we have raised a battery upon the bowling green near Mount Edgecombe, another upon Teats Point, going into Catwater. Likewise a battery at Mount Batten and planted guns in them, and also put four in an old blockhouse upon Passage Point, going into and now ourselves in good condition to receive the French if they make any attempt upon us. This morning we saw the French fleet, and therefore manned our battery upon the bowling green with seamen, and sent a detachment to strengthen the four guns (Cawsand), which, believed, might the first place they might land upon. Also sent fifty seamen to the Royal Citadel manage the guns there, and as many more to St. Nicholas (Drake’s) Island. On Justice Calmady’s request, I sent six guns to Sand (Bovisand) Bay.” Intercepted letters from the French fleet showed that adverse winds prevented any siege of Plymouth being made and they ultimately departed unchallenged as there were not enough English ships at Plymouth to engage them. This may have concentrated minds even more given that only the weather prevented the French making an attempt on Plymouth. In 1691 work began on the new dockyard at Devonport which was complete by 1693.

The Island was very busy throughout this period and manned constantly through to the end of the war in 1697 and on until the death of William in 1702 and throughout the reign of Queen Anne. Treasury papers show Major Henry Hook, Lieutenant Governor of Plymouth as “conveying the reliefs of guards to St. Nicholas Island” from 1690 through to 1702 authorised by both the Earl of Bath as Governor until 1696 and thereafter by Major-General Charles Trelawney who was appointed “to be Captain and Governor of the town of Plymouth and Captain, Governor or Keeper of the Royal Citadel there and of all forts and fortresses there and of St. Nicholas Island and the castles and forts therein during pleasure”. Government papers show that in addition to the garrison at Plymouth and St. Nicholas Island were authorised two Master Gunners and 18 gunners. By 1697 the French and British declared a truce and came to terms for peace. Boundaries were largely unchanged in North America and India but the big gain was the abandonment by France of support for the Jacobite claim through James II son James meaning the succession of William was largely secure. By 1700 a regular payment was authorised for fire and candle on the Island indicating it was being continuously manned. During the war the Island not only housed the defensive garrison but was also used to house troops being transported to theatres of war in India and the Americas. The barracks, built a century before, were designed to house 300 men it is quite possible more were crammed in as the Island would have been a temporary barrack prior to deployment. Papers from the time show how busy the Island must have been as on at least one occasion a request to accommodate more troops had to be turned down as the Island could not sustain any more men.

Although the war had finished in 1701 it was proposed to formally reorganise the batteries in the area to provide for the defence of the new Dockyard with two batteries at St Nicholas Island, one of nineteen and the other of fourteen guns. These would be integrated with a battery at Mount Edgcumbe of twenty-four guns and of one at Stonehouse of eleven. Although some plans were drawn up in 1693 it is most likely the batteries on the Island were simply a reorganisation of existing batteries and firing points. A battery would simply have described the number of guns and firing points rather than any major new works on the Island. Indeed I haven’t been able to find any records indicating new works on the Island and major changes to the buildings aren’t shown on any Island plans or drawings until after 1720. This tends to support the idea that the gun batteries were reorganised rather than any major works.

William died in 1702 to be succeeded by Anne, the second daughter of James II and we were quickly at war with the French again as the King of Spain died without an heir and Europe broke into factions supporting various claimants. Anne therefore spent most of her reign with a number of allies including Hapsburg Spain at War with France and Bourbon Spain in what was known as the War of the Spanish Succession. Britain’s aim was to prevent the French taking control of Spain and hopefully expand our own Empire into the bargain. Indeed when the war ended between Britain and France in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht Anne did quite well out of it. The French conceded Canada and some of her Caribbean colonies whilst Spain conceded Gibraltar and Menorca to give naval bases for operations in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. Anne died the following year in 1714 paving the way for us to invite another foreigner over to be King. This time the Elector of Hanover George.

For the Island this must have been a manic period. The Island was constantly manned with relief guards, cannon, gunpowder and shot all increasing the firepower available to defend Plymouth and Devonport. Add in a large throughput of troops being transported to various theatres of war who would all have needed extra stores and rations just to sustain them bearing in mind everything we take for granted, water, light, heating would have to be taken over to the Island by boat and it must have been an extremely busy time. The permanent garrison also saw its role change from defending Plymouth and the Cattewater to concentrating on defending the new naval dockyard at Devonport. Next week the first major changes to the layout of the Island as buildings begin to be moved from the top of the Island to the western end.