In the early 1700s as trade and empires increased so did voyages across the great oceans and the Island would play a small part in Britain being the first country to navigate the world accurately. The problem of latitude, the fixing of a position North or South of the equator had been solved. However the fixing of longitude, the fixing of a position East or West of the Greenwich Meridian was unsolved and Mariners were relying on direction and speed (dead reckoning) to fix their position from a known point of latitude. However cumulative errors after a long voyage frequently led to shipwrecks, loss of life and economically importantly cargoes. Whether it was from the cost of a replacement war or merchant ship and loss of equipment or cargo shipwrecks cost a lot of money. For an Island nation reliant on a growing overseas Empire and ocean going trade routes for its financial security it was important for the British above all to solve the problem, not least as it would give both our Merchant and Royal Navies a key edge over our Imperial rivals. The tipping point came in 1707 when an error in determining longitude caused four British naval ships to run aground 28 miles west of Lands End on the Scilly Isles. Around 2000 men including the commander of the fleet, Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell were lost. Subsequently in 1714 the Government passed the Longitude Act offering a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could devise an accurate method of determining longitude, joining the Spanish, Dutch and French who had also each established a prize for solving the problem in the hope of being first to solve the problem whilst their rivals were still flummoxed by the problem.

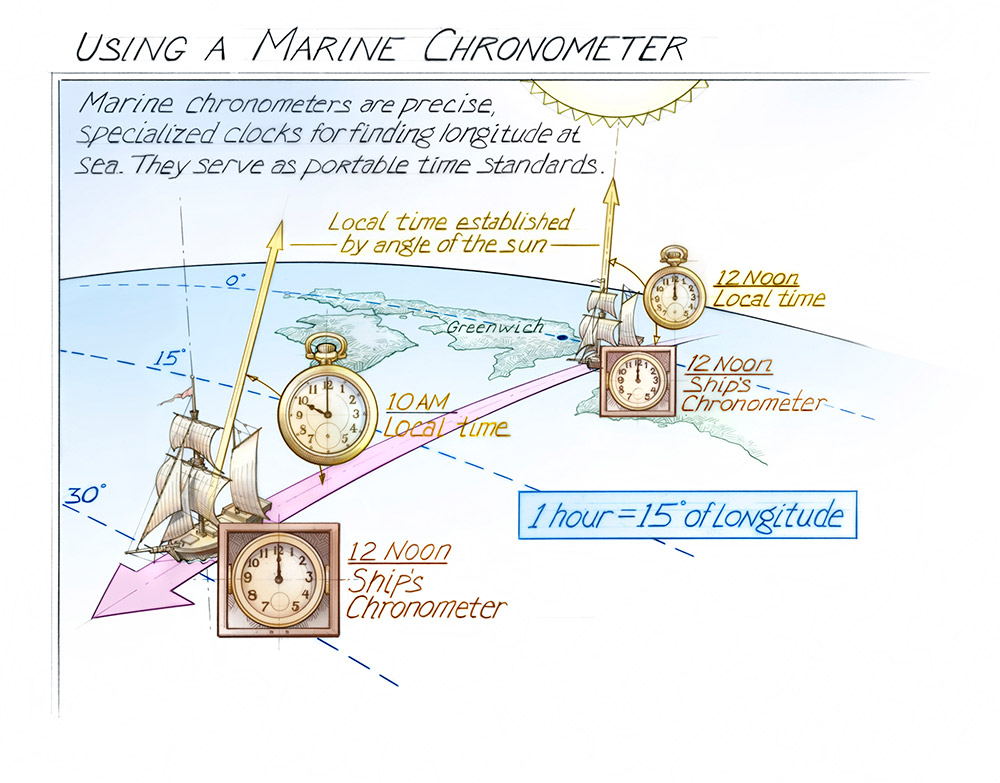

In theory fixing longitude could be done by knowing the time at a fixed place on a line of longitude. In the case of Britain the observatory at Greenwich near London which happened to run through the Prime Meridian. The ships Chronometer would always read the time at Greenwich. At noon (Greenwich Time) on the ships Chronometer local time was established by the measuring the angle of the sun of at noon. Then comparing local time to Greenwich Time gave a time difference. Knowing 1 hour equalled 15 degrees of longitude meant that the longitudinal position could be fixed either east or west of the Greenwich Meridian depending if the local time was earlier than noon (west) or later then noon (east). Hence the importance of an accurate chronometer that was robust and could operate under severe weather conditions and atmospheric conditions whether in extreme hot, cold, wet or dry climates.

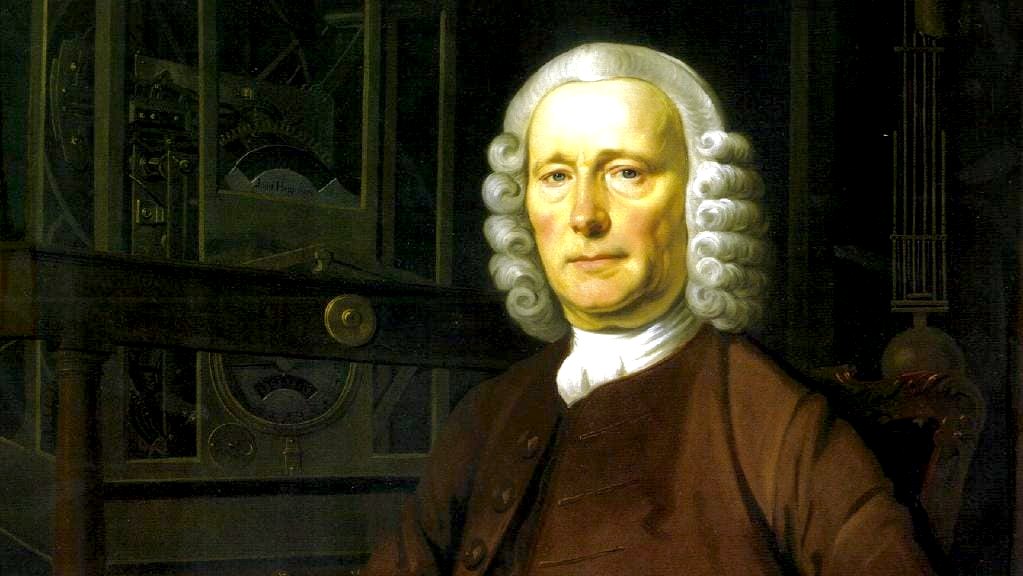

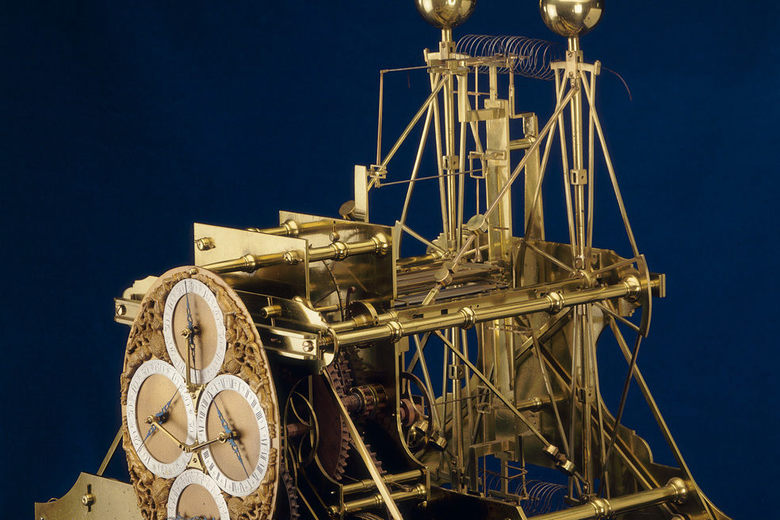

By 1725 an English watchmaker, John Harrison began working on the problem. He realised a clock to determine longitude would have to be strong enough to work accurately in an unstable environment, a ship being buffeted by bad weather, at varying temperatures and in different climates. Five years later in 1730 he produced his first chronometer, known as H1 which contained mechanisms to compensate for temperature and ship’s motion. It had enough promise for the Government to give him grants to develop the chronometer. By 1763 his final design, the H4 had solved the problem. But Mr Harrison was only part awarded the prize as the Government decided the grants he had been awarded for research should be partly offset by deducting them from the prize money. The Government also felt that his sea chronometers were not viable as they were too expensive, up to a third of the cost of a ship itself. With Harrison bitter about the prize money and feeling he was not being fairly rewarded he was less than forthcoming about the manufacture and workings of his chronometer.

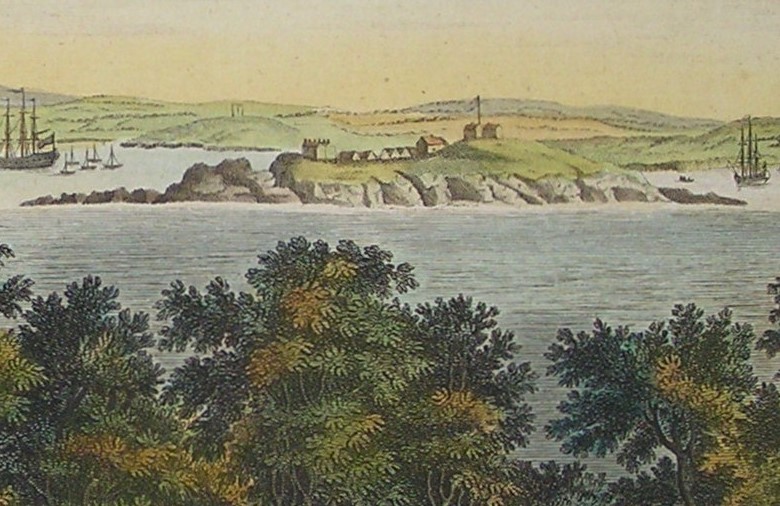

However knowing the chronometer worked and the problem being one of time to manufacture and cost in 1765 the Board of Longitude asked 6 expert watchmakers to witness H4 working. The hope was one of them could duplicate and manufacture it quicker and cheaper than Harrison’s efforts. Amongst those selected was wonderfully named Larcum Kendall. Kendall’s replica along with 3 by another watch maker John Arnold were to be assessed on Capt Cook’s second South Sea Voyage starting out in 1772. The chronometers were used in conjunction with the relative positions of the Moon and other planets and St Nicholas or Drake’s Island was used as the reference so an Observatory was set up on the Island to take the required measurements. Alex Finlay’s 1845 memoir mentions an observatory on St Nicholas Island and that Mr Bayley (an assistant at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich) and who accompanied Cook on his voyage made observations from there. The observatory is likely to have been just a defined observation point marked on the ground or on a building and would not have been a separately constructed building. The most likely spot is the top of the Island which would enable measurements to be made at any time of the day. Back then there would have been no trees, shrubs or other large flora on the Island as these were all imported onto the Island in the 1970’s so the Island would give a clear all round view. However there is no record of exactly from where on the Island Mr Bayley took his measurements.

William Wales, an astronomer, who was also on Cook’s voyage recorded in his log on 3rd July 1772 that he “Went on shore to Mr Bayley at St Nicholas Island, where I found he had got up his Clock and Quadrant and was employed making Equal Altitudes for the Time and Zenith distances for the Latitude of the Place. In the morning got on shore the Transit Instrument with intent, if possible to observe a few transits of the moon over the Meridian for to find the Longitude of the Place from whence we are to take our Departure by the Watches. Cloudy with Rain at times”. Captain Cook’s voyage proved the accuracy of Larcum Kendall’s chronometer, K1, the other three chronometers manufactured by John Arnold were not as reliable.

On his return from this voyage he Cook wrote to the Secretary of the Admiralty (and wrote in his ship’s logbook), that “Mr Kendall’s watch has exceeded the expectations of its most zealous advocates”. He pointed out that, thanks to the accuracy of the K1 he had been able to make accurate charts of the South Sea Islands for the first time. Captain Cook called the K1 “my trusted friend” and later wrote: “I would not be doing justice to Mr Harrison and Mr Kendall if I did not own that we received very great assistance from this useful and valuable timepiece.” Kendall went on to refine the manufacture making cheaper models faster but without losing accuracy. On his third voyage from 1776 to 1780 Captain Cook took one of these simplified versions which would later be used by Matthew Flinders from 1801 to 1803 when he circumnavigated and charted Australia. Chronometers were introduced to all Royal Navy ships by 1825 giving them an advantage over the French and Spanish ships which did not use them.

Although the Island is well known for its fortifications I love this part of its history and the albeit small part it played in solving one of the great problems of the day. I think it is amazing that nearly 250 years ago Richard Bayley was on the top of the Island making scientific calculations to test a device that would prove to be the answer to solving the problem of longitude and enabling our ships safely navigate the oceans. Next week I’ll talk about the world’s first recorded submarine fatality which happened just off the North East shore of the Island.