Once hostilities were declared in the English Civil War Plymouth proclaimed itself for Parliament. It was quickly isolated from the surrounding regions of Devon and Cornwall which were held by Royalists and soon found itself besieged. The siege lasted almost continuously from 1642 to 1645. Key to its successful resistance was holding the strategic point of St Nicholas Island and control of the Navy who had declared for Parliament leaving the Royalists with few ships. This allowed the regular arrival of supply ships and parties of sailors to be rushed ashore through Millbay to reinforce the defences when under attack, all under the protective guns of St Nicholas Island.

At the start 1642 Plymouth was a strongly walled town with a long history of resistance to the Crown especially by its traders against the taxes the Crown imposed. Fortunately the Island seems well fortified as a report of the same year stated that a bulwark of exceptional resistance crowned the summit of the Island. As it became clear war was going to break out the mayor added an outer line of fortifications along the northern ridge running west to east from the old Stonehouse creek north of Mill Bay, to Lipson and Tothill that forms a crescent of around 4 miles around the town. The Corporation in the absence of the Royalist Governor of Plymouth and St Nicholas Island seized the Island and appointed a Parliamentarian, Sir Alexander Carew who held estates locally as its commander.

Every man in Plymouth signed an oath to die in defence of the town as the Royalists began to take control of Devon and Cornwall. Rumours ran wild of children slaughtered, women raped and men sold into slavery in towns that fell to the Royalists which were reinforced by the tales of the refugees. Soon the population of Plymouth rose from 7,000 to 10,000. Every man, woman and child was forced to work to build fortifications, dig trenches and supply the soldiers with ammunition, food and drink. Strong drink was provided when the fighting got bad and it did indeed get bad. Once Plymouth was hemmed in by Royalist troops at Saltash, Plympton and Mount Batten living conditions inside the town became unbearable, with only the port able to supply food and fuel to the trapped inhabitants. The taking of Mount Batten meant the entrance to the main port (where the Barbican is now) could be fired on by the Royalists but Millbay could still be used as long as the town held St Nicholas Island. The Royalists also blocked the fresh water supply from Dartmoor which led to plague and typhus spreading amongst the population. Firewood ran out but Plymouth refused to surrender. A Royalist trumpeter who arrived to demand the town’s surrender was whipped, beaten and imprisoned overnight before being released and advised not to return!!

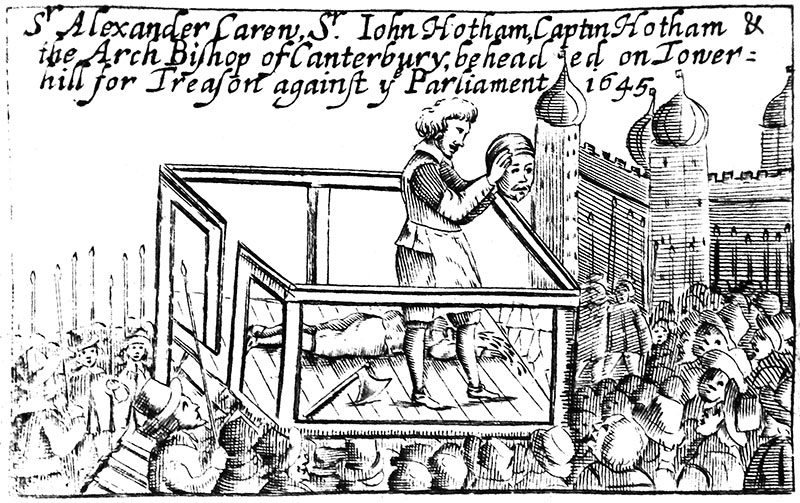

By May 1643 Royalist victories at Stratton and the capture of Bristol confirmed the Royalist command of the South West. This concerned Carew greatly and fearing he would be on the losing side he entered into negotiations with the Royalists to surrender the Island in exchange for a pardon and being able to retain his estates. The Royalists agreed but Carew delayed wanting his pardon confirmed in writing with the Royal Seal. Word of Carew’s plot now reached Philip Francis, Mayor of Plymouth, possibly from Carew’s servant. Francis now had Carew watched by Sgts John Hancock and Benjamin Fuge. As his suspicions grew Francis sent 2 ministers, Wills and Randall, to the Island to urge the Sgts to take precautionary measures against Carew. They found the Sgts had already seized Carew and were waiting to transfer him to Plymouth Gaol. Hancock was promoted to Captain while Carew was sent to the Tower of London, tried, found guilty and beheaded on Tower Hill in late 1644. It’s unclear who commanded the Island once Carew was arrested, some reports suggest Hancock had temporary command but if he did it seems either Colonel Wardlaw who was Commander-in-Chief of the town or Colonel Gould eventually took command.

Over the 4 years the defenders won many victories, Colonel William Ruthven, a Puritan of the Plymouth militia took 300 mounted men circumventing the Royalists in Plympton and took their Modbury headquarters by complete surprise scattering the 900 Royalist guards. The Plymouth forces then captured the senior Royalist officers, the largest group of Royalist senior officers captured. In December 1643 Prince Maurice was in charge of breaking the siege at Plymouth. He saw Laira Point overlooking Laira Creek as a weak point in the defences. The Royalists attacked at night and overran the Parliamentary guard putting the Parliamentary supply ships moored in the Plym River in danger. Hearing the alarm, the Parliamentary forces in Plymouth mustered to counter-attack. Using the cover of night they surprised the Royalists’ but eventually were forced to retreat west to near Freedom Park. The Royalists now crossed Laira Creek to take the town, but the Plymouth forces regrouped and counter-attacked again. A report of the time states they “swept all before them like a roaring torrent”. The Royalists now retreated only to discover that the tide had turned and the Laira Creek was impassable. Trapped against the creek the Royalists were shot and drowned as they tried to escape across the Laira. At this point they were also targets for the ships still in the Plym estuary and many Royalists were taken prisoner. There is a monument to the victory at Freedom Fields.

In disgrace Prince Maurice moved on, and in 1644 Sir Richard Grenville was appointed to oversee the siege on Plymouth. Sir Richard was seen as brutal even by the standards of the day and was not alone in switching sides during the conflict. Initially Grenville declared for Parliament and received an appointment to lead an army. However he changed sides taking his forces and Parliament’s money with him to join the Royalists. Grenville lived up to his sadistic and corrupt reputation. He became a war profiteer, kidnapping rich men in Devon until their families paid a large ransom amassing a personal fortune in land and money and was known to hang prisoners of no value. In January 1645 he launched a large attack with over 6,000 men. However the weather intervened, it rained for two days filling the ditches with water and turning earthworks into mud. Grenville sent in his forces repeatedly only to see his men and horses cut down or drown in the mud. When one of Grenville’s own officers protested at the useless loss of life, Grenville ran him through with his sword. The attack eventually petered out. Later in the year as Parliamentary forces gained the upper hand and the Royalist Commanders fell out – Grenville was imprisoned for failing to follow orders and refusing a command – a relief force of 8,000 Parliamentarians lifted the Siege. Two victories at Naseby and Langport effectively decided the war for Parliament and Charles I was eventually handed over by the Scots in 1646 ending the Civil War. Although hostilities flared up again in 1648-1649 Parliament was again the victor and hoped to settle the matter decisively by trying Charles I for treason. 59 Judges, known as the Regicides, found him guilty and he was subsequently beheaded.

Although the Island wasn’t directly attacked during the siege it was key in enabling Plymouth to hold out. If it had been betrayed by Sir Alexander Carew no fresh supplies or reinforcements could have been bought into Plymouth by the Navy and the town would have fallen. In turn this would have allowed the Royalists to redeploy the significant forces they needed to maintain the siege. However Parliaments and later Cromwell’s rule as Lord Protector wasn’t going to end well either as we shall see next week when the Army had a major falling out with Parliament leading to the restoration of the monarchy when Charles II used the Island as a state prison.

I just want to thank you for this lovely informative work. I am doing an essay on Plymouth during the siege and to find this well written work about St Nicholas Island has helped me greatly as I have been reading the pamphlets that were written at the time, like Colonel Grenville and Sir Carew. And as you are aware there is not much out there about the island and how important it was to the success of the siege, thank you again

Hi Emma, you’re welcome and thanks for the kind words. We are trying to share the Islands collective history as far as we can and it’s gratifying to know it is of use.

Hello again!

I am emailing you with an enquiry about Sir Alexander Carew. Could you tell me whether Sir Alexander was connected the Carew family of Antony House?

Kind regards

James Frondella

Hey

Yes he was part of the Carew Family of Antony House and his portrait hangs there. My research is the Island only so I can’t tell you much about the wider Carew or indeed Alexander outside his involvement with the Island in the Civil War

Hello Bob. I am currrntly doing a project on Plymouth in the Civil Wars and the Sabbath Day Fight which is moving along nicely. However I was wondering if you might have any information as to what dates the Creeks of Lipson and Stonehouse were filled in? I do know from Phillip Photiou that the infill for these two creeks was taken off North Hill but when exactly this work was undertaken I have no idea. I would imagine it was quite a bit later in either the 18th or 19th Centuries. Any information to this end would be most appreciated.

Many thanks

Mark Stephenson

Hi Mark, Stonehouse creek was started late 19th Century after complaints throughout the mid to late 1800’s about the overflow of sewage. The main issue was there were the 3 different town boards all using the creek for sewage disposal and a consensus wasn’t reached util the turn of the century. Victoria Park was opened 1903 so the works were completed by that stage. Lipson Creek was reclaimed in the early 1900’s all part of a general upgrading of the sewage works around Plymouth or the then 3 towns. Don’t have anymore than that I’m afraid byt google books can often throw up a few helpful snippets.

Do we know anything about Colonel William Ruthven? Was he a Scotsman?

Hi Kenny. Yes he was a Scotsman and may have been related to the Earl of Gowrie Ruthvens but I can’t confirm that. He arrived in the South West with a force of 200 scottish mercenaries and were hired by the Plymouth Town Council who made him Military Governor. The scottish were professionals compared to the local militias and were amongst a large number of Scots who fought on the Puritan Parliamentary side as King Charles was a common enemy. If you google Colonel William Ruthven there is a fair bit about his Civil War exploits.

I Found This really interesting Bob, Thanks especially when linking it to the Southwest Langport etc.

Thanks