1800 marked the beginning of the 19th Century, George III was on the throne and we were involved in the War of the French Revolution against the French Republic and Spain that continued until 1808. After France and Spain invaded Portugal in 1807 the Spanish revolted and it morphed into the Peninsular War with a number of Coalition Wars allied with a varying number of States until Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo in 1814. As part of these wars we fought against Denmark which resulted in Norway and Denmark splitting to form independent countries whilst the East India Company expanded the British Empire in India. We also found time to defend British Canada against the USA and burn down the White House while we were at it.

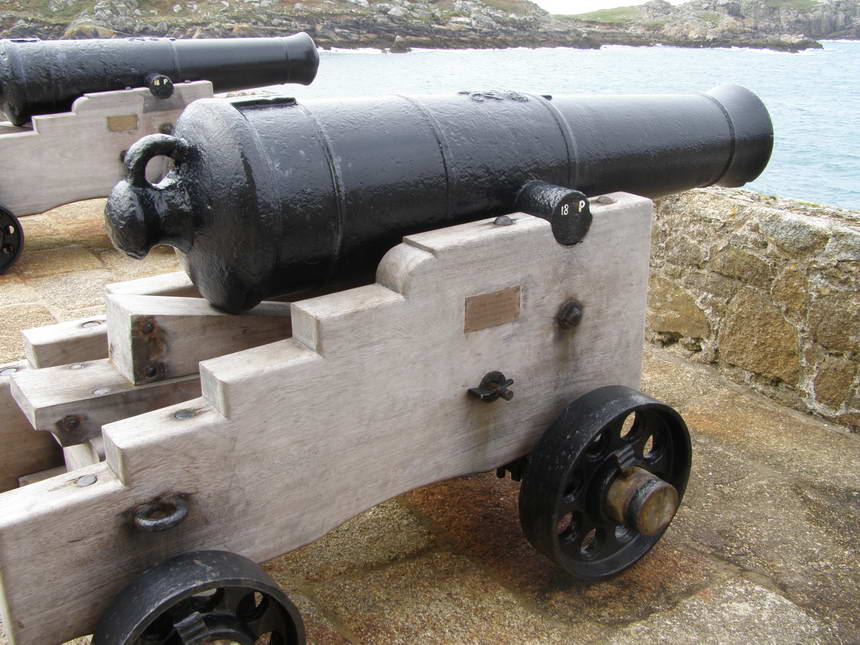

On the Island there were 4 different governors from 1800 to 1814 however Western Military District, along with others covering the whole of Great Britain, had been created in 1793. The Governor was now a titular post with only ceremonial duties. Military power over the Island and Plymouth now lay with the General Officer Commanding Western District, usually a Major-General towards the end of his career who was also the Lieutenant-Governor of Plymouth. The Island itself had batteries around the Island as well as on top of the Island. The barracks, Guard Room and stores were now down at the Western end of the Island, some of which are still standing. An 1805 report listed 22 x 32 pounders on the Island another report states an additional 6 x 18 pounders were on the Island. If there were 28 guns on the Island it would have required 140 gunners plus officers to man them. At this time the Artillery Garrison was drawn from the Invalid Companies of the Royal Artillery. The Artillery was organised into Battalions and Companies and an Invalid company was smaller than a Regular Company, It was commanded by a Captain, assisted by a Lieutenant and Sub-Lieutenant with a Sergeant, Corporal, 2 Bombardiers, 4 Gunners and 31 Matrosses plus a drummer. A Matross was ranked below a Gunner and assisted in reloading the Gun but also acted as infantry to defend the Gun. Given the numbers it seems the Invalids could man at most 6 or 7 guns so it appears as the Army was stretched by the number of overseas commitments the Island had a smaller permanent garrison to be augmented by the Militia that still existed as the reserve forces of the UK if the threat increased. Dock workers at Devonport were also trained to fire the Guns and were part of the reinforcement for the Island. There were also infantry units on the Island. The 41st of Foot, part of the Corps of Invalids were on the Island as early as 1777 but the Corps was disbanded in 1802 although some men continued to serve in support roles if they were fit enough. For clarity the Invalid Companies of the Royal Artillery were separate to the Corps of Invalids and continued to be the Artillery Garrison until around 1819. The next mention of an infantry unit is in a newspaper report of 1809 which reported on a Grand Ball held on the Island by the Dorset Militia, part of which was stationed on St Nicholas Island. It seems at least some County Militias were initially called up to defend Britain whilst the Regular Regiments were abroad. The Somerset Militia must have taken over the Island Garrison duties at some point as in 1811 newspaper reports have them replaced by the 2nd Battalion of the 61st (Royal South Gloucester) Regiment. Their duty stations are shown as Maker Heights and Dartmoor Prison in addition to the Island. The likely size of the St Nicholas Island detachment would be at most a company of between 80 and 90 soldiers commanded by a Captain. The combined garrison could have been up to about 125 or more depending on the size of the infantry detachment with 43 Artillerymen and up to 80 or more infanteers. Overall command would be in the hands of the most senior officer and in the case of equal rank who was promoted first rather than the preserve of either the Artillery or Infantry. The age of some of the soldiers varied, drummers were often young boys but a death certificate of 1813 shows that Barrack Sgt Durham had served in the Army for 70 years and was 88 years old when he died on the Island. He was most probably originally part of the 41st Regiment of the Corps of Invalids who were disbanded in 1802 but was kept on to do the specific post.

The life of the militia would not have been a harsh as the regular soldiers who would have been disciplined, regimented and subject to the whims of their Officers. Their pay would have been minimal especially after deductions for food, equipment, losses and repairs. A Gunner could expect around 1 shilling a day with Sergeants 2 shillings, an infantry soldier would only get 8d per day. For comparison an unskilled labourer would expect 2 shillings a day, however there were some jobs available to the soldiers for extra pay such as an Officers Batman (servant) for the Private Soldiers and running accounts for any literate and numerate NCO’s. They were also provided with only one uniform and the quality would depend on the Commanding Officer. Although there were water cisterns, sometimes called wells constructed at various times on the Island water was untreated even if bought over from the mainland. The soldiers had a daily allowance of beer and rum to try and prevent the spread of disease which were both watered down to try and prevent drunkenness. The soldiers would have a small allowance of bread or flour, beef and rice or oatmeal for 2 meals a day which they would have cooked themselves, normally by arranging themselves in small groups or messes of 5-6 men often led by a Corporal. To augment this they would club together to buy any other items, potatoes, vegetables, coffee or sugar for example for their mess. The Island had a couple of boats to collect stores from the victualling point at Cattewater Harbour (the Barbican area) and then Royal William Yard once it was open around 1830. There was a landing place and slip close to where the current entrance is on the Island today. However often they had to buy from a Sutler (a civilian merchant) who was licenced and supervised by the Commanding Officer. The Sutler would also supply personal items such as tobacco. The Sutler would rent a building or room at a rate regulated by the Articles of War and could make a profit selling goods. They were subjected to military law and in the same way as any soldier and this was sometimes formalised into giving the Sutler a rank. There was a Sutler on the Island by 1806 as a letter from Captain Rogers of St Nicholas Island was sent to J Hawkins, possibly a magistrate regarding the conduct of William Phillpot, “Mr Philpott sutler at this Island is a private soldier in my company of the 24th Battery as such being subject to martial law I will take care to that he conducts himself as he ought to do”. It seems Pte Phillpot must have got himself into trouble requiring his CO to try and get him released. The letter is in the Plymouth Archives and is difficult to completely decipher but the Royal Artillery was organised into Battalions sub divided into Companies commanded by Captains at the time.

The barrack room that was home was crowded, wooden double bunk-beds with a minimum of space between them lined the walls with tables and benches running down the middle. On the Island there was a fireplace in each room and the earliest record of heat and light is from 1789 Parliamentary Papers which state £211, 5s 7d was paid to Andrew Clinton for supplying coal, candles etc to St Nicholas Island from 25 Dec 1787 to 24 Jun 1788. Each bed had a straw-filled pallaise as a mattress, two blankets, and a rug. The rest of the furnishings consisted of a rack for the muskets (there was no armoury although they didn’t keep powder with them), shelves and pegs (three feet two inches long per man) to hang knapsacks and uniforms on, fire irons, a coal- or wood-box, a wooden tub used for personal washing which doubled up as a urinal, a candlestick, and a broom and mop. The stench would have been noticeable from the wash tub or urinal and from the men themselves. There was no box or cupboard in which to put personal possessions as soldiers were not expected to have any personal belongings. The barracks were where they cooked, ate, slept and socialised. In addition to their daily duties or fatigues, guard, drill and maintaining the fort and guns soldiers could find themselves being used to keep the peace or in coastal areas to combat smuggling. Additionally they could be on personal tasks for their officers or hired out by and for the profit of their officers to local tradesmen or farmers. Discipline was severe even for minor offences and dealt with summarily by regimental, district or general courts martial. Boredom was a key factor leading to the majority of problems, drunkenness or misbehaviour associated with drunkenness and low pay led to theft. One common punishment was “Running the Gauntlet”, being flogged by the regiment whilst running between 2 lines of soldiers. Desertion was common and any deserter found would be branded with the letter D. Medical treatment was limited and soldiers often relied on the few wives that accompanied their husbands. None of these conditions would change until the army reforms of Cardwell and Childers of the 1870’s and 1880’s. It was a thankless often unrewarding life and regular soldiers, especially in times of peace, were viewed by the general public as the dregs of society.

In 1811, as a wartime precaution all ships not belonging to the Royal Navy had to land their gunpowder at St Nicholas Island and the following year the Mayor of Plymouth concerned at the amount of gunpowder being held by its citizens issued a proclamation against keeping gunpowder in houses in Plymouth and that it was to be stored in the magazine on Drakes Island. The Garrison would have seen a number of boats run aground on the Island. Although it’s likely the Island would have been the site of a number of earlier groundings or wrecks we now have reports from the newspapers of such events. In 1803 the Brig Integrity literally carrying coals from Newcastle was aground but managed to get refloated with limited damage, the following year the Olive Branch carrying wine from Oporto in Portugal suffered the same fate but also got away with minimal damage. In 1808 the Matilda wasn’t so lucky her cargo of hides and tallow had to be unloaded and it was expected to break up although I couldn’t find a follow up report to confirm that happened. In 1811 the Junge Albert carrying wine and Juniper Berries had to be unloaded but was saved and went for repair. The grounding of ships seems to be a not uncommon event and the main cause mentioned was either running to close to the Island or missing of an anchorage near to the east of the Island after which the ship is blown onto the Island by wind or tide or both. The occasional body was also washed up during this time, in 1806 it was reported from Plymouth in the papers that “The body of a man, supposed to be that Lieutenant Rutherford, for whose apprehension a reward was lately offered, has been picked up at St. Nicholas Island, in this port”. There were no details as to what he was wanted for, how he died, whether it was an accident or foul pay was involved, if he was Navy or Army and if so what Regiment he was from. At the time Army Infantry Officers purchased their commission and had to pay for promotion but were often the second sons of the upper class with very little income or inheritance. Many who had their commission purchased by their family sold them when they could to get some available cash. Gambling was prolific and debts were not uncommon so maybe he was on the run from debts when and died in an accident trying to escape his abroad. Unfortunately the papers didn’t always follow up the stories in those days but if I find any more information on Lieutenant Rutherford I will update you.

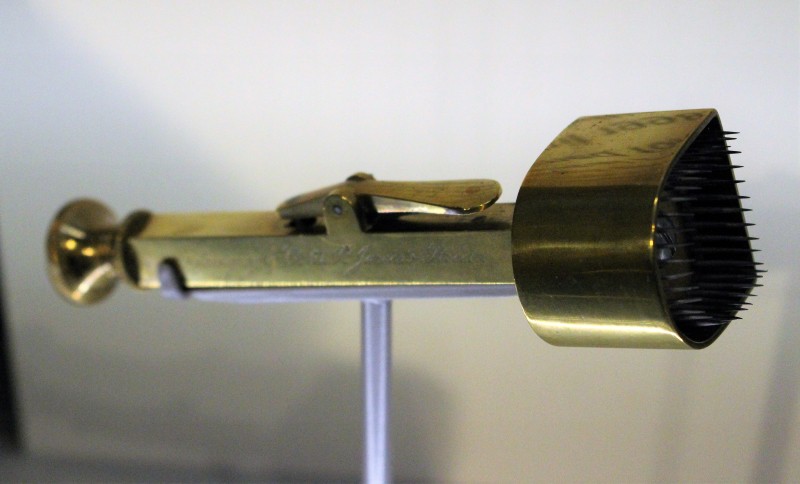

Finally to end this blog there was a duel on the Island in 1809. Duelling was still a popular means of setting honour until the 1830’s and was not finally outlawed until. The local papers ran the story as follows “Sunday evening last, a duel was fought at the back of St. Nicholas, or Drake’s island, near Plymouth, between two midshipmen belonging to the Princess Charlotte frigate, now lying the Sound. The cause of their dispute we have not yet learnt: they exchanged three shots each, at five paces distance, and were reloading for fourth time, when the Commandant of the Garrison interfered, took away their pistols, and sent them on board their ship. One of them appeared much inebriated, and was in the act chewing musket ball to make it fit the pistol, when the Governor very properly interposed his authority”. What they mean by the back of the Island is unclear but my guess is it would be on the South facing Cornwall. The main buildings were on the West and the entrance was where it is today on the North or Plymouth facing side. It doesn’t surprise me at least one and probably both were drunk. Throughout the ages both Officers and Squaddies have fallen out over imagined insults when drunk, had a fight and within seconds of the fight ending been best mates again. Obviously in those days it could end in death but being drunk they’d probably be lucky if they could aim properly, they hadn’t hit each other after firing 3 times from 5 paces which meant when they extended their arm their opponent would only have been a couple of metres away from each other. Hopefully they weren’t training to be Gunnery Officers.

We are now not only seeing the major events that affected the Island but getting a bit more nuanced view of life on the Island for the ordinary soldiers that lived there. Next week I’ll cover up to 1850 which was a period of peace in Europe but numerous small conflicts in the Empire during which there was more major construction on the Island and of course I’ll cover more Ripping Yarns and Garrison Follies as well.