This final set of memories from the Adventure Centre days is again provided by Martin Dunning and I am very grateful to have had the chance to meet Martin on the Island a few days ago along with a number of other Adventure Centre Islanders who sent in their memories that I have been able to share. A huge thank you to them all.

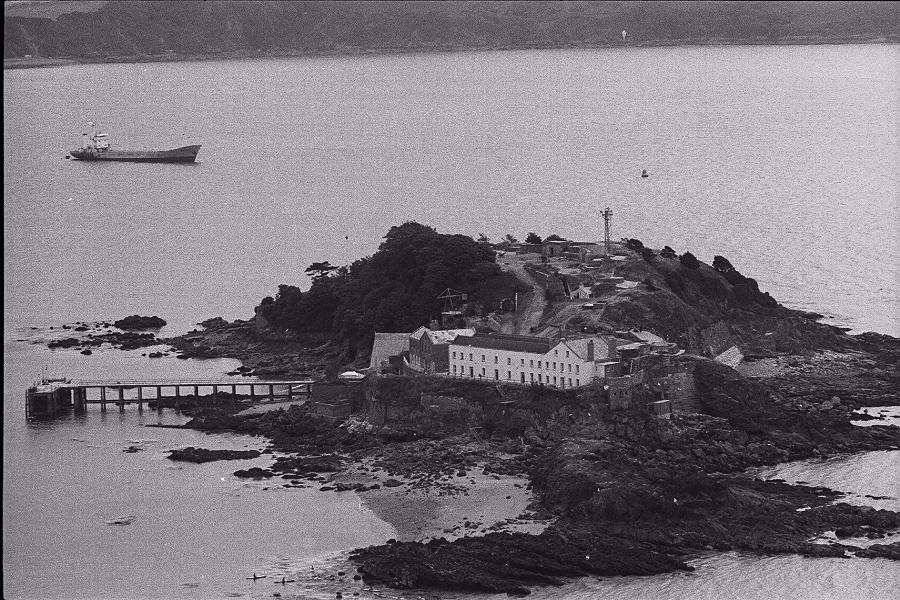

Martin takes up the story from here on in. “By the end of the 1979 season I had reached the exalted status of Senior Instructor in the climbing department. Pete, who had originally given me the job in April, had left mid-summer and his deputy had stepped into his shoes, thereby promoting me a notch. I seem to remember that this elevation was worth a whole £3 a week. With the departure of the last group of Dockyard apprentices at the end of September the season was over and instructors departed too – some to Plymouth Polytechnic, others to more permanent jobs and some, like me, to an uncertain future. That night I received a phone call from the Warden; the new Head of Climbing had left following a ‘difference of opinion’ and would I be interested in taking on the job? I didn’t need to be asked twice and the next day I was back at Mill Bay for the early boat. I had very little idea of what I was letting myself in for, a winter on the Island was a very different kettle of fish from a summer season. In the season, we might have had 30 resident staff and 84 resident students, plus non-res students and the daily staff such as the Youth Opportunities lads and their foremen. The latter were still visiting on a daily basis, completing the quay, boathouse and other building projects. In terms of resident staff there were just seven: the Warden, the Chief Instructor, the Bosun, and four Heads of Department. The cooks had left, the big kitchen in the western end of the dormitory block was closed, and life for the winter staff revolved around the Island House. On the ground floor was the office, which led through to the Chief Instructor’s flat, above which was the Warden’s accommodation. The rest of us lived on the first floor, where we shared a tiny bathroom and an even smaller galley-style kitchen. We took it in turns to cook, the quality of the meals varying depending on who was cooking”.

The highlight of that first winter was having no water. RMAS Pintail was re-laying the NW Drakes buoy when it pulled up the Island’s water pipe on its anchor. They at first denied any responsibility but several eye-witnesses came forward and HM Dockyard had to cough up for a complete new pipe to be laid at a cost of £14,000. Unfortunately, the new supply wasn’t laid until the spring which meant that for a whole winter, we had to bring every drop of water over in jerrycans, which took a lot of time and effort. Every few days we would all make our way to the Mayflower Centre for showers, but given the physical nature of a lot of our work I fear we were a less than fragrant bunch that winter. The shipping channel had to be closed for a day for the new pipe to be laid from Firestone Bay across to the Island and I can still remember the excitement of turning a tap that evening and having water come out.

Two winters later, Pintail pulled the same trick, only this time with our mains electricity cable, which meant a few dark nights before QHM supplied us with a generator. This was to allow their camera, which kept an eye on things coming down the river, to operate. Every day we had to check oil and coolant and refuel the generator, and while doing this one morning I suddenly found myself eyeball to eyeball with an almost incoherently irate MOD policeman, who was screaming at me to turn the generator back on. It turned out that there was a nuclear submarine coming down the river, and that just as it reached the Narrows I turned off the generator to do the checks and the QHM’s screens went blank. They were understandably twitchy about the nukes, but we did suggest that they let us know next time one was moving, only to be told that they didn’t like releasing that information.

There was a lot of work to keep us busy, repairing dinghies and kayaks after a whole season of heavy use; mending waterproofs and lifejackets; getting the workboats out and giving them their annual overhaul; ordering new equipment; redecorating the dormitories and all the briefing/teaching rooms; upgrading the climbing wall, and a thousand other things. We worked hard in what were often awful conditions and with limited resources, but I don’t remember anyone complaining too much, or any fallings out; the shared suffering forged a strong bond between us all. Having a social life was complicated. The last scheduled boat was at 5pm in the winter, and after that we had to fend for ourselves, which usually meant three or four of us taking one of the boats and tying up either in Mill Bay or the Barbican for the evening. Certain rules were always observed: no one was ever to be left on the Island by themselves; on returning somebody would always help the boatman put the boat on the mooring; and whoever was driving the boat had to be the responsible adult and drink less. In reality, the latter usually meant drinking one or two fewer pints than everybody else, but boat handling had become like breathing for most of us and so we rarely had any trouble. There was the odd hiccup – one evening we got back to Mill Bay to find that thick fog had reduced the visibility to 20 metres or so. The compass bearing for the island was 180° and we knew how long the crossing should take. However, there was a strong ebb tide running, which meant allowing for leeway, and it seemed prudent to keep the speed down. These two factors actually threw out the possibility of making any accurate calculation so it was a case of flying by the seat of our pants. I set the throttle to half and nosed out into the murk. After 11 minutes I cut the revs to a quarter, then to idle, and coasted along in flat calm as we squinted into the fog. Eventually, after what seemed an eternity, we came to a halt on the rocks below the oubliette with a bump so slight it didn’t even scratch the paint. We had missed the end of the jetty by perhaps 15 metres.

Fog was only an occasional hazard. Heavy weather reared its ugly head far more often, and there were often periods of two or three days when we were confined to the island as it was too dangerous to run the boats and particularly to bring them alongside the jetty. The first storm I experienced was in 1979. Our two Musketeers were still out on the moorings but had had their masts lowered and put into storage in the boathouse. The storm blew through overnight and the following morning I drew back the curtains to check on the boats and realised that Venturer was no longer there. We spent the morning in Chocy combing the Hoe, the Cattewater and Devil’s Point but to no avail. It was only in the afternoon that we found Venturer, on the south side of the Island below the buttress. How she had ended up there was a puzzle as it meant she had actually gone upwind after her mooring shackle broke. We spent a miserable afternoon in the surf trying to get a temporary patch on the enormous hole in her hull before floating her off for Chocky to tow her round to the quay, where we hauled her out. We all hoped she could be patched up but in reality she was mortally wounded and never sailed again. That night, with the weather deteriorating again, the Warden decided that we couldn’t risk Chocky and asked if any of us would be willing to take her over to the safety of the Barbican. My girlfriend at the time lived on the Barbican, and the Head of Sailing had friends he could stay with ashore, so we volunteered, something we very nearly came to regret. Chocky was underpowered and under ballasted which made her skittish in any sort of sea; in a cold winter Force Eight she was terrifying. The sea was was bad enough, but when it came to turning in round Fisherman’s Nose, wind over tide was causing big, steep breakers and there were a hair raising few seconds when it looked like we were in danger of being pooped before we got in and commenced breathing again. We tied up in Sutton Harbour and made a beeline for the Dolphin.

The really big storms, of which we had two or three, were something else. The storm on the night of the Penlee Lifeboat disaster – 19th December 1981 – was the most violent thing I’ve ever witnessed. The wind was gusting to over 90 knots and merely leaving the sanctuary of Island House took some doing. The battering from the wind made even breathing difficult and standing was impossible so we crawled to the top of the buttress, about 80 feet above the sea. Enormous storm waves were breaking on the buttress and the spray was being carried right over the Island. The ferocity of it was indescribable and though we were on terra firma and only half a mile from Plymouth Hoe it felt very much like we were at the edge of the world. We lived with the sea day in, day out, and the experience of that storm and the loss of the lifeboat had a profound effect on all of us.

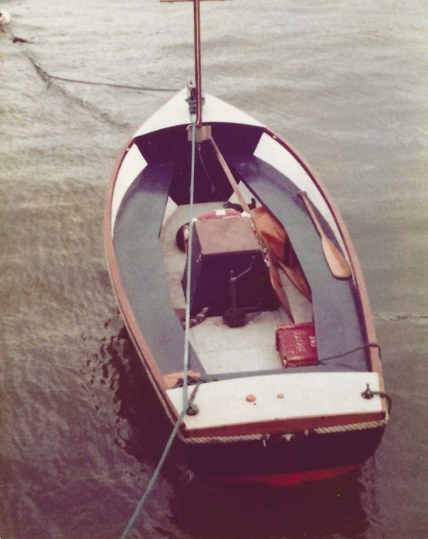

Boats were the Island’s Achilles heel. The budget was always tight, and the expense of running and maintaining a small fleet of boats was considerable and the resupply routine absorbed a lot of man hours. The Bosun’s department – staffed in the summer by the Bosun and a couple of non-residential part time boatmen – was responsible for ensuring that our lifeline ashore was kept running and that there was always a safety boat available to cover the sailors. The three workhorses were Chocky, Little, and Mallah. If all three were in service, everything was fine and all the bases were covered. Take one out of the equation and everybody started to feel a bit nervous as that left no slack in the system. Given the hard, relentless usage the boats experienced, it’s not surprising that from time to time one or the other of them would complain. By far the least temperamental was Little: open, clinker-built, sturdy and a fantastic sea boat, powered by a trusty two-cylinder Lister diesel and steered by a tiller. She was the first boat with whom I became acquainted; that summer she was ever present as safety boat for the sailors, her engine straining to keep up on windy days. It was at the end of the day, delivering a boat load of kids back to the jetty, that the safety boat driver let go of the tiller, raised an eyebrow in my direction, and suggested I bring Little alongside. I took the tiller as nonchalantly as I could, knocked the throttle back, as I’d seen done many times before, and coasted in. A brief snort astern at what I hoped was the right moment, and she came to a halt alongside. Beginner’s luck. As I walked back up the jetty I realised my hands were shaking.

Everybody loved Little – her character, her reliability, even her Island livery of dark blue hull and white gunwhales – which is what made her ‘upgrade’ in the winter of 1980/81 so unpopular. We had received a grant from somewhere and it was decided that she need a cuddy and wheel steering, which was duly done by the new Bosun. There was no doubting the quality of his work, but a modern cuddy design on a fifty-year old hull just didn’t look right and worse, all that extra weight and windage topsides drastically impaired her seaworthiness and handling. Now, she wallowed in any kind of swell, and the cuddy acted as a sail, making coming alongside a real handful. The aft end of the cuddy had a racy little cut out, with a sharp corner perfectly placed at head height. We complained about it as an accident waiting to happen, only to be told by the Bosun “you know it’s there”. A couple of days later he spectacularly split his head open boarding on a rough day. Stitches – several of them – were obviously called for, but the Bosun protested that he was terrified of needles. By this time, however, he was looking a bit like a character from a Sam Peckinpah movie, so we ignored his protests and whisked him off to the Royal Naval Hospital, prepared to physically restrain him while he was stitched up. As it happened, he took one look at the hypodermic the nurse was pointing in his direction and fainted clean away, enabling the deed to be done without trouble. Chocky was the load carrier. I can’t remember exactly how many passengers she was licensed to carry but it was around 20. If the passengers were Island staff, she could be driven by anyone capable, but if they were kids on courses, they fell into the category of “fare paying passengers” and therefore the boat could only be helmed by someone with a Department of Trade and Industry boatman’s license. It wasn’t only passengers that Chocky carried, of course, and probably half her journeys involved carrying supplies of one kind or another. On Tuesdays, the cooks made their weekly trip to the cash and carry, returning with a minibus full of food which had to be loaded onto her at Mill Bay and then unloaded at the jetty and carried by a crocodile of staff all the way to the kitchens. Building supplies, chandlery, stationery, and 42-gallon drums of diesel were among other items carried, the latter being lifted out using the old white hand-wound crane on the end of the jetty. When Chocky broke down, it tended to be spectacular and at the most inopportune moment. In my first summer, she was constantly plying back and forth carrying materials for the boathouse. One day the strain became too much and the engine blew up. I was out on a Wayfarer with three kids and saw a huge cloud of black smoke, followed by Chocky listing violently to port, Absurdly, my first thought was that she’d been torpedoed but it transpired that when the engine blew up everybody on board rushed to port to escape the smoke, nearly capsizing her. A new Perkins diesel and a big hole in the Island’s finances was the result. On another occasion, she was being used as safety boat for the sailors when the engine died in a big swell just off the Shag Stone. I was sailing one of the Musketeers and ended up having to take Chocky under tow back to the island. Luckily it was a windy day. The last I ever heard of her was a couple of years after I left, when a chance encounter in the Dolphin with one of the lifeboat crew revealed that she had broken her moorings and ended up wrecked in Barn Pool.

Mallah was possibly the most eccentric of the trio. She was an open 18 foot Plymouth Pilot, powered by a single cylinder Sabb diesel, which ticked over at only 50rpm, meaning you could hear each ignition of the cylinder. The engine had a huge flywheel and as a result the starting handle could give a vicious kick back which nearly dislocated your thumb. In addition, to start up in cold weather involved the use of ‘starter cigarettes’, phosphorous pellets which were put into a holder that was then screwed directly into the cylinder block and ignited on compression. Inevitably, these would get wet and starting Mallah up could be a real trial in winter. Her final eccentricity was the absence of a gearbox; in its place was a variable pitch propeller which in theory could be put into reverse at full revs. The only time I tried that the effect was not unlike that of sitting on a bucking bronco and everybody ended up in the bilges. I didn’t try that again. The picture was completed by a small cast of bit part players. There was a 16-foot dory, powered by a Johnson outboard so unreliable that it meant the dory really needed its own safety boat which was a problem as the dory was supposed to be a safety boat anyway. There were several small pram dinghies which we used as tenders to get out to the moorings and back. This was fraught with possibilities as a good breeze and tide could make it touch and go as to whether you reached your destination, and on one occasion, rowing furiously against a stiff easterly, I saw the last of the mooring buoys slip past just out of reach and ended up on the beach in Firestone bay. I trudged, cold and wet, up Durnford Street in search of a phone box, realising as I did so that my wallet had somehow ended up in the drink, and had to make a reverse charge call to the Island so that someone could come and rescue me. Happy Days!

I suppose every collection of memories should have a chapter titled ‘Stupid Things We Did’. In our case, there were plenty, none of them monumentally stupid, rather the ‘Larking Around’ variety. I wouldn’t do any of them now, but they were done in the self-belief of youth and that mindset, though it may get you into trouble, will more often than not carry you through a scrape. I should say at this point this applied only to staff exploits and that we were all very responsible when there were kids around. However, at weekends, or in the winter, or on our rare days off, we would regularly stick our necks out. Lots of the Stupid Things revolved around boats and the sea – like the time we took Venturer through the channel between the Island and Little Drake’s. Anybody who has lived with the sea knows that a little misjudgement, an ill-timed gear failure, or just plain old bad luck, can really get you into trouble, but I don’t remember anybody ever suffering more than the odd bruise or a dent to the ego. Which is lucky because by far the majority of Stupid Things came about when the weather was less than clement.

Heavy weather seemed to stimulate everybody’s sense of adventure. For the canoeists it meant waves and the bigger the better; for the sailors the attraction was the power a rig (even reefed down to the bolt rope) can generate; and for everybody it was a chance to stretch ourselves and improve our skills in what were less than perfect conditions. With regard to the latter point, our larking around in heavy weather certainly made us better canoeists, sailors, and seamen/women in general, which in turn meant we were safer when we had a boat full of kids. Hoisting the spinnaker on the 470 in a force six was probably not a good decision. It was ok while we were in the lee of Mountbatten, but as soon as we poked our bow out from the end of the pier, Fido really got the bit between her teeth. Bob was out on the trapeze, I was out at full stretch on the toe straps and there was nothing we could do but hold on and enjoy the ride as we scorched past the Hoe. We ended up in Barn Pool, still, to our surprise, upright, and as we came into the lee we were able to finally douse the spinnaker. I’ve never gone so fast under sail (and not much faster under power) and I’m sure we were well in excess of the 10-knot speed limit!

A big swell was guaranteed to get the canoeists’ attention. The back of the Island, given a southerly swell and an outgoing tide, can produce some fine waves. Unfortunately, the area is strewn with reefs and as an added complication there are the WW2 anti-submarine defences to contend with in the shape of the Dragon’s Teeth (or is it Shark’s Teeth? – I can never remember). Oh, and a wrecked barge. And a strange pillar thing that was almost covered at high tide. And sundry other obstacles, all of them hard and most of them pointy. Surfing these waves required a high level of skill (which I never quite attained) and a high degree of local knowledge. A couple of instructors took every opportunity to sit at the top of the buttress or above Razor Blades Bay and study the waves in all conditions of swell and tide and waited for weeks for the right conditions. When the right swell finally arrived, at the end of one summer, the results were spectacular: big, glassy waves with barrels which would apparently swallow up one or other of the canoeists before spitting them out unharmed. The rest of us sat at the top of the cliffs and watched, torn between admiration at their balls and horror at their foolhardiness. It lasted only about half an hour before the falling tide made it too dangerous, and I never again saw there such perfect waves.

Another source of amusement in a big swell was the deep gully on the south side of Little Drake’s. The requirements for this were a wet suit, a buoyancy aid, a canoeing helmet, and a strong belief in your own immortality. Just getting to the gully was an undertaking in itself: down the wooden steps (long since gone, I imagine) outside the canteen and then across the channel to Little Drake’s, where you would spend several minutes teetering above the seaward end of the gully and waiting for the right wave before jumping. If you timed it right, the wave would carry in and up, rising as it was squeezed between the narrowing walls of the gully, and deposit you on a ledge just below the top of Little Drake’s. Points were awarded for nonchalance and the non-use of hands.

My most ill-advised episode occurred on a still, flat autumn night and was prompted by the prospect of a hot date ashore. The only problem was the visibility, or lack of it. We’d had persistent fog for a couple of days and indeed the previous night I’d managed the unlikely feat of getting lost between Island House and the dormitory block. I came down the ramp to answer the telephone, which we’d forgotten to switch through upstairs and found myself in a complete white out, unable to even use the ringing phone to guide me as the sound was refracting and distorting weirdly in the fog. I became completely disorientated and blundered round for a while until I bumped into a wall. The phone had stopped ringing, so I used the wall to guide me back towards the ramp, wondering where the doorway I expected to find had gone. Eventually it turned up and I was able by feel to recognise it as the door on the north east corner of the dormitory block. I was at least 20 metres from where I had thought and moving in the opposite direction. The next night the fog was, if anything, even thicker but, undeterred, I decided to go ashore. Using any of the boats was out of the question, the boss said, adding jokingly that I could always paddle over if the girl in question was really that hot. Well, she was. I didn’t think he was being serious but I took him at his word, taped a compass to my spraydeck and set off, my eyes glued to the little luminescent dots that told me I was heading due north. It was slack water so I didn’t have to allow for the tide, the sea was eerily smooth, and I soon settled into a rhythm, the only noise that of my paddles dipping into the water. The fog was actually quite low-lying, clinging to the surface of the Sound and perhaps only ten metres thick, allowing the full moon to illuminate my little bubble so that it felt strangely like being on the inside of a ping-pong ball. Usually when crossing to Mill Bay you had to keep eyes open for other traffic but on this occasion that wasn’t going to be a problem – nobody in their right mind would be out in this visibility. As I approached Mill Bay, however, I became aware of the noise of engines, and strained my eyes into the mist to avert a collision, only to discover that it was the sound of the generators aboard Armorique, the Brittany Ferry tied up on the dockside. Now that I knew where I was, it took only a couple of minutes to locate Trinity Pier, haul my canoe out, and change into the tidy clothes I’d stowed in a black plastic bag behind the cockpit. Unfortunately, I’d neglected to put in any shoes and had to head off for my date wearing yellow sailing wellies. On my way over to the Barbican I phoned the Warden to let him know where I was; his silence on the other end of the phone was more eloquent than anything he could have said. My date didn’t mention the yellow wellies.

Once again huge thanks to all who contributed and these memories will be preserved as part of the Islands heritage. They will be more in the coming weeks from the dark days of the World Wars as I have come across some new information from those times.

Thanks for those memories Martin, I worked with you as an instructor for a season in about 1980, I’ve searched several times for an ex- DI staff page but never found anything. I have fantastic memories of my time there.