This week is another bunch of memories from 1979 to 1981 from Martin Dunning who was a climbing instructor at the time. Martin provided so many good stories so there’ll be more from him next week.

I was 22 when I went to work on Drake’s Island in April 1979. A friend of mine was head of climbing; they were short of instructors and Pete phoned to see if I wanted a job for the summer. At the interview we drank coffee and talked about climbing for a couple of hours and Pete said I’d be starting the following Monday. No HR, CVs, or references. On the Monday in question I turned up at Millbay docks which then was a working, if slightly run down, commercial dock. The Island boat left from Trinity Pier and that first day I heaved my belongings onto Sir Egbert Cadbury, a 32 ft Cheverton workboat, which was slightly underpowered by its four-cylinder Perkins diesel. Known affectionately as ‘Chocky’, she was the Island’s workhorse, running from 0800 every morning to ferry staff, food, building materials, chandlery and everything else that was needed to supply the Adventure Centre. In early April there were no courses running – that was still a few weeks off – and so my first lunch was taken in the dining room at the western end of the barrack block with around 20 staff. The food was good but I was aware that there was a bit of an atmosphere and it turned out that I had arrived at the end of an acrimonious falling out between the senior staff and the Warden. I was never privy to the circumstances but by mid afternoon the Warden had packed his bags and left on Chocky, and I was left wondering what I might have let myself in for.

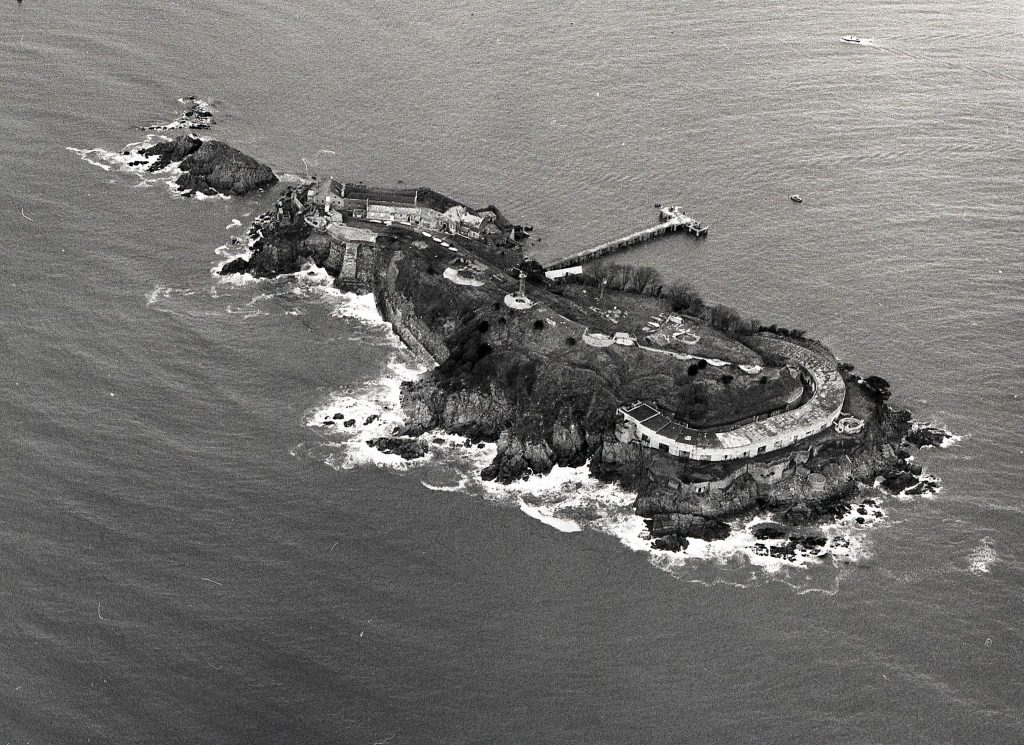

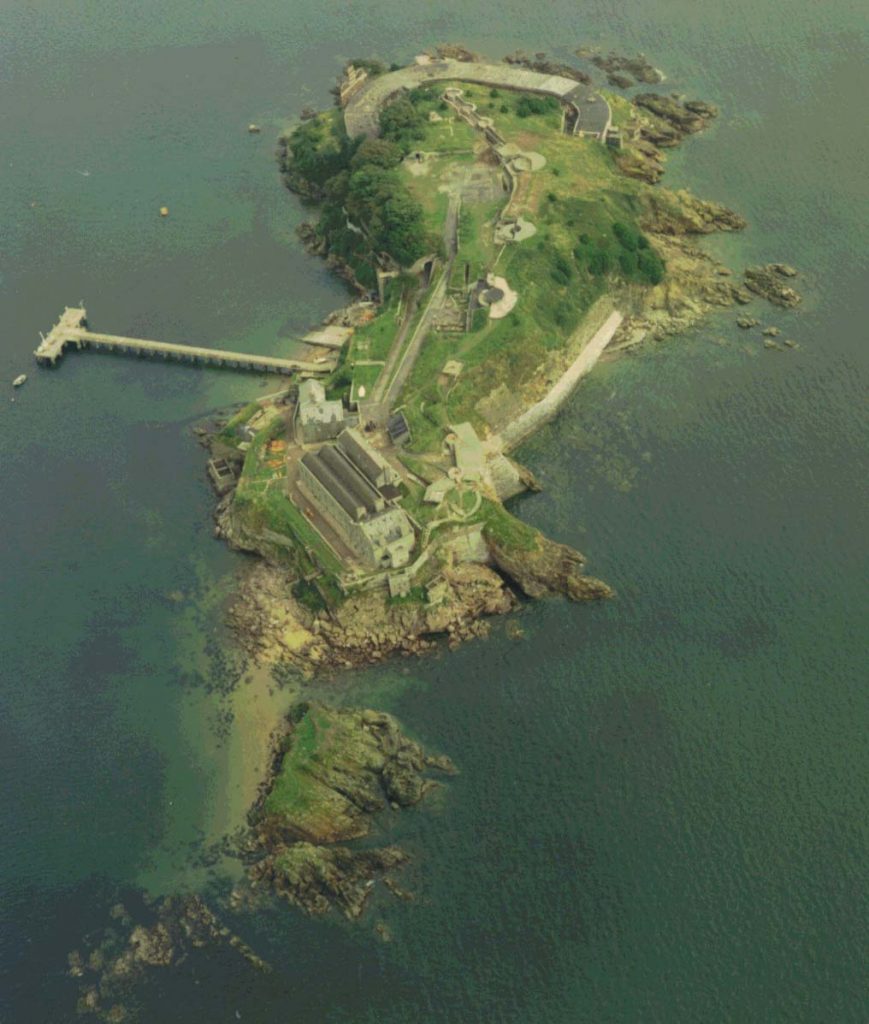

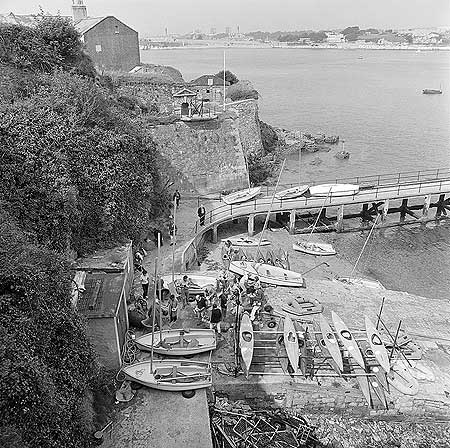

The next few weeks were pretty hard work. We were finishing building the climbing wall on the moat wall behind the casemates and most days involved mixing concrete, chipping out old pointing, and lugging what seemed to be an endless amount of supplies up from the boat. At the time the old steel stairs up to the jetty were well past their sell by date – steep, narrow, rusty, pitted with holes and generally downright dangerous. Plans were afoot for them to be replaced but it couldn’t be done until after the season was over so for the time being we had to grit our teeth and get on with it. The hard standing to the west of the jetty was being built by the Youth Opportunities scheme, and the boathouse was going on top of that. This meant tonnes, literally, of sand, cement, concrete blocks and assorted building materials had to be carried down the steps at Mill Bay, loaded onto Chocky, and unloaded onto the jetty before being carried to wherever they were needed. We were young and strong but it was punishing. We came to regard it as hard labour and the Island as our Alcatraz – a nickname that stuck.

Every few days we’d have a day or two of staff training as a reward for our efforts. We climbers spent a lot of time scrambling up and down everything suitable, getting to know where we’d be teaching our charges when they arrived. The climbing wall was short and fierce with one or two routes that were genuinely hard. On the back of the Island was the buttress, easy angled but big enough (50ft?) to give real feeling of adventure for a primary school kid abseiling down above a big swell before climbing back up again. A more spectacular abseil was that from the crane buttress above the hard standing – maybe 60 feet hanging out in space, though for us instructors the worst bit was inching out along the steel beam that formed the jib of the crane to rig the slings in the first place. The torpedo chute in the casemates provided hours of fun trying to get up it without using the rails on each side, and general messing around in the tunnels could occupy a wet afternoon.

The complete traverse of the Island at water level provided a good challenge. Best done around high tide in order to soften the landing, it started from the slipway and went clockwise all the way round before ending on the beach by the jetty. The highlight was Razor Blades Cove to the west of the casemates and at the southernmost point of the Island. Here, an overhanging wall striated with veins of hand-shredding quartz had to be negotiated; few attempts ended bloodless or dry shod.

The first groups of kids arrived sometime after Easter. The non-residential groups were almost exclusively primary school groups from the Plymouth area and arrived each morning with their teachers and a packed lunch, going back home each evening after their day of activities. Residential kids stayed on the island, arriving on a Sunday evening and leaving on the following Saturday morning. They came from far and wide and were almost exclusively secondary school groups. Wellington School, Cheltenham College, Tiverton Comprehensive and USAF Chicksands were among the regular visitors, coming back year after year and bringing up to 72 kids and perhaps 12 staff. We got to know them all quite well over the years. All the kids were brought over on the Lady Elizabeth, one of the tourist boats, with the familiar livery of blue hull, white superstructure and red funnel. She plied her way from the Mayflower Steps to the Island several times a day, seven days week in the season, putting ashore each time she tied up 50 or 60 tourists who would picnic on the beaches and spend money in the little shop up by the QHM’s mast. There was something of a love/hate relationship with the tourists – we needed their money but having them wandering around the steep, unfenced slopes was a distraction we could do without, and in the nesting season they would get attacked by seagulls and then blame us. It was usually with a sense of relief that we watched the last tourist boat of the day depart.

Daytime activities were broadly climbing, sailing, canoeing, marine biology and caving and tailored to age and ability. Once the non-res kids had left at five o’clock there was dinner, and then evening activities from 1900 – 2100. There was volleyball, treasure hunts, jetty jumping (assuming the tide was high enough!), a film once a week and on Friday a disco in the enormous vaulted underground magazine. The vagaries of the weather obviously played their part and there were plenty of times when both day and evening activities had to be hastily rescheduled if a storm blew through or it was raining particularly heavily.

As an instructor, life was pretty busy. All the kids would line up outside the dormitory (barrack) block at 0900hrs and the duty instructor would despatch them to their respective instructors for the day. They were divided up into groups of 12, each group named after a local worthy such as Scott, Drake, or Raleigh. Taking res and non-res into account we did on occasion have 10 groups – 120 kids – which represented quite a logistical challenge and required huge numbers of lifejackets, waterproofs, kayaks, paddles, ropes, harnesses, helmets . . . Keeping track of all the kit and keeping it in good repair was a massive task and we tried to have someone on maintenance every day just to keep on top of it. Once you’d done your daytime activity there was a good chance you’d be working in the evening, either on the evening activities, or as duty instructor. If you were on evening activities there was a chance you could get off for a pint on the 9pm boat. There was no such let up if you were duty instructor. Being DI (as it was known) involved being on call for 24 hours and responsible for everything from the morning muster through first aid, plumbing and electrical problems to homesickness and kids misbehaving in the dormitories. DI or not, we all put in a lot of hours in an average week. 70 or 80 hours wasn’t in any way unusual and none of us were paid any overtime. When I started, I was being paid £20 per week, we were fed and housed for free and that therefore that £20 was beer money. A pint was about 40p. We quite often ran out of money before pay day. There was a definite party culture, driven in part by visiting staff with the residential groups, who were on holiday and intent on having a good time. Somehow, we managed to fit in the long hours and the late nights and still be fresh for instructing the next day.

‘Basic’ is probably the best word to describe the kids’ dormitories. Plywood bunks, fitted with bed boards just like the ones they used to line the tunnel in ‘The Great Escape’. Whitewashed walls which never quite hid the fact that the dormitory block was on the damp side, and bare light bulbs. None of the kids ever complained though and I suspect it was all part of the adventure for them. Our accommodation wasn’t much better. My first room was on the first floor of the dormitory block, on the south east corner directly above the staff room. It contained a creaky bed with a mattress of about the same thickness as a pizza base, and a wardrobe which went out of shape every time you opened one of the doors. The kitchen bins were in the alley outside so on a hot day the smell was unpleasant, there was a constant racket from seagulls fighting over food scraps, and fag smoke from the staff room crept up through gaps in the floorboards. None of it ever kept me awake though; by the time I made it to bed the fresh air, the activity and the partying had taken their toll and I would be dead to the world. Most of the underground space was utilised for one thing or another but there was one bit that was strictly out of bounds, not that that stopped us investigating it when the Island was quiet in winter. This was the Armada display, accessed down a staircase which started somewhere up by where the guns are now mounted on the top of the Island. Somebody had obviously put hundreds of hours into creating this model, which occupied a space of perhaps 25 feet by 10 feet and was a representation of the naval action that saw off the Spanish. I have no idea who built it but it was the centrepiece of the Island’s museum which, for the first season that I was there at least, saw a steady stream of visitors who would be shown round by one of the tourist guides.

When I arrived on the Island I had little experience of boats, be they of the sailing or powered variety. As a climbing instructor I assumed that I wouldn’t be increasing my experience in the nautical sphere. How wrong I was. By the end of that first summer, I had probably spent three or four days a week sailing and at least one day a week as duty boatman. It all boiled down to a numbers game, basically. A group of 12 kids could be supervised by a couple of instructors if they were canoeing, climbing, or studying marine biology. To take a group of 12 sailing was far more labour intensive, probably involving four or five instructors. We sailed two types of boat when I arrived. The Wayfarer, at that time the workhorse of sailing schools and adventure centres and still seen often today, is a 16-foot dinghy which was usually on the Island crewed by an instructor and three kids. Often derided by instructors for being slow and boring, and given plenty of unflattering nicknames, it was in fact a great boat for novices: seaworthy, stable and generally well behaved. We had 8 or 9 of them, all with yellow hulls.

The fleet was completed by two red-hulled Musketeers – Venturer and Chase – which were French built, plywood keel boats of 22 feet. They would usually be sailed by an instructor and 4 or 5 kids. I learned to sail in about three weeks flat. One of the other instructors was a keen racer and wanted to race Venturer in the Plym Yacht Club Friday night series. He was a bit of a martinet and consequently always short of crew. I was willing to learn, and didn’t mind (too much) being shouted at, and discovered quite quickly that I had a natural aptitude for sailing. It didn’t occur to me, however, that I would be instructing, until one morning when the Chief Instructor informed me that one of the sailors had gone sick and that I was his replacement. It was quite a daunting prospect, the idea of being in charge of a Wayfarer and three kids, but I reasoned that there were plenty of other boats around if anything went wrong (which it didn’t) and that if all else failed I could get towed back by the safety boat (which didn’t happen either, at least not that first day). A day sailing unfolded in the same way every time – until you got onto the water. There was the kitting out of the kids with waterproofs and lifejackets, followed by a short briefing, and then out on the water by 1000hrs. The Musketeers had moorings off the end of the jetty, and there were six moorings for Wayfarers a little more to the east. These moorings were in the lee of the island, and the wind could swirl around from any direction; this, combined with a strong tidal flow, made getting off and (particularly) back onto the moorings very tricky, especially as none of the boats had engines. Kids and instructors were ferried out by the safety boat. This was usually Little, a 21-foot open clinker-built work boat powered by an ancient but ultra-reliable 2-cylinder Lister diesel. The job of safety boat driver was always noisy and smelly (old marine diesels aren’t renowned for their refinement) and usually slightly stressful. Standing instructions were to keep the flotilla as close together as possible but on a rough day, and particularly when going upwind, the boats tended to scatter, which prompted the safety boat into charging around like a fretful sheepdog trying to round everybody up. Once aboard, sails were hoisted and off we went. The day’s destination was dictated by the weather and tides. If it was forecast to be particularly breezy we would stay in the Sound or perhaps go up the Tamar, but the most visited port of call was Cawsand. With the prevailing wind being south west, that meant a morning sailing upwind before we pulled the boats up the beach (the Wayfarers) or anchored them (the Musketeers). Cawsand was the perfect lunch stop when the wind was in the west as it was so sheltered, and it had one other advantage – a beach café. With us bringing perhaps 20 kids ashore, most of whom wanted to buy chips to supplement their packed lunches, we were a useful source of revenue for the café, who would often give us instructors free cups of tea. Weather permitting, we ranged far and wide, usually trying to avoid the feared lee shore at lunch time. If the wind was in the east, the sheltered bay of Jennycliff might be our destination, or Bovisand further out, and on the odd occasion when weather and tide combined favourably, Cellars Beach at the mouth of the River Yealm. To the west, where the coast is more exposed, options were more limited, but we did on a couple of occasions make it as far as Whitsand Bay. On days and evenings off, boats were often used recreationally by staff. The Musketeers could sleep four reasonably comfortably and were sometimes used for a weekend away – as long as they weren’t being raced. The Friday night series became something of a fixture for Venturer, and despite our relatively green crew we finished third. We also had the use of a 470, a two-person trapeze dinghy, which provided more than its fair share of thrills and spills. On one occasion, while surfing down huge swells off Picklecombe, we capsized in spectacular fashion and spent some time righting the boat. As we headed back in, baling energetically, we saw the inshore lifeboat heading towards us. An onlooker had called the coastguard who had in turn radioed the lifeboat, who were out anyway and popped over to escort us in. We asked if they would disappear before we came in sight of the Island to spare our blushes and a possible dressing down from the Warden.

Being ticked off by the boss was always a possibility – we were young, and high spirited, and in our free time tended to push the boat out, as it were. One Friday evening, out for a lazy sail in Venturer in the last of a dying breeze, Chris came up with an idea. Between Little Drake’s and the Island proper is a narrow, rocky channel and sand bar. We had all canoed through the channel and had even, on a very high spring and calm conditions, sailed a Wayfarer through, taking care to jink round the big rock just below the surface at the entrance. Tonight was a very high spring tide with no swell and the water was as clear as gin. Venturer was a sizeable boat, with a draft of about three feet, so it was a risky undertaking and would be a very tight squeeze. I was sent on to the foredeck with my Polaroids on and shouted directions to Chris as we crept through with inches to spare. As we slipped over the sand bar, with clear water ahead of us, I heaved a sigh of relief and then saw, leaning over the musketry wall, the Warden’s face. ‘Apoplectic’ would probably be the correct adjective for him, while irresponsible, immature and insubordinate were the ones he applied to us as soon as we got ashore. He didn’t let us forget it for weeks, but I don’t regret it. I bet nobody else has ever done it!

Many thanks for sharing your memories Martin, these are a great addition to our archive and the history of the Island, more to follow next week.

Martin, this is a fabulous account & wholly accurate. I joined your team in late May that year and Martin Northcott was our CI by then – he’s known by a few here in Scotland from their time at Bangor.

I also remember, amongst hundreds of mainly happy times, the Warden Chris who was arrested for embezzlement in my third season!

Anyway how are you?

My email is andycloquet60@gmail.com

Hi Andy

Bob here the Blog author, I don’t know I’ll send your details onto Martin as he may not visit the page.