Once the monarchy was restored in 1660 Charles II decided to secure the throne by changing laws to favour the Crown, emasculating any opposition by ensuring his supporters were in all the positions of authority and showing he was not to be challenged with overt displays of power. All three came into play to some extent on the Island.

One of the first things Charles could and did do was to imprison those in power during the Commonwealth for treason. Part of this included making dual use of St Nicholas Island not only as a fort but also as one of a number of State Prisons. As Plymouth had held out so long for Parliament and had been a religious nonconformist or Puritan hotbed this was probably intended as an overt warning to Plymouth that opposition would not be tolerated. Although small in number, probably only 9 in total, the prisoners were all high profile including the senior nonconformist clergy from Plymouth. The first prisoner was Colonel Robert Lilburne, a senior Parliamentary Commander who had been one of 59 regicides who signed the Death Warrant of Charles I. The last prisoner, Major-General John Lambert died on the Island in 1684 when the Island became solely a fort again.

In 1661 the Corporation Act was passed which required all office holders to swear allegiance to the Crown and renounce the covenant. This effectively prevented any nonconformists from holding office. In places such as Plymouth which had been thoroughly puritan he ensured that his own supporters were appointed to replace them. The most notable appointment was John Granville 1st Earl of Bath, a Royalist Military Commander who was appointed Governor of Plymouth and St Nicholas Island.

Charles also needed a restored State Church. To reinforce his position it needed to be anti-nonconformist and preferably more in line with his views on worship. Although he was a bit of a playboy with a whole bunch of Mistresses including not only the famous Nell Gwyn but also a Moll, a Hortense, a trio of duchesses, a couple of actresses and a few daughters of the nobility including partying and extra-marital affairs in the new forms of worship would probably have been a step too far. However as head of the Church he could make it impossible for the nonconformist ministers to preach effectively which he did through a number of laws essentially making it illegal to preach except under the auspices of the Church of England. In 1662 the Act of Uniformity was passed detailing how the Church was to carry out its functions. Nearly 2,000 churchmen refused to sign it. The authorities, now in the hands of Charles, persecuted them and some of the leading churchmen in the Plymouth area were imprisoned on the Island.

Although some reports suggest up to 12 prisoners were held on the Island I can only find definitive proof of 9 prisoners. Most were held less than a year and the most held at any one time was 6 over a period of 9 months from 1665 to 1666. As said Colonel Lilburne was the first prisoner in 1661. The prison population doubled to two when James Harrington was imprisoned later in the year. Harrington was a republican philosopher who wrote Oceana, a utopian pamphlet which vexed the decidedly monarchist Charles II. Harrington was advised by a doctor to take the drug guaiacum in his coffee as treatment for Syphilis. After following this advice he became very ill. A side effect of the drug can be dementia and as his health worsened he was released a year later in 1662 when his relatives posted a £5,000 bond. He lived until 1677 although he was often described as suffering from “intermittent delusions” or “simply mad”.

Colonel Lilburne died in August 1665 just before the nonconformist ministers who were imprisoned for refusing to sign the Act of Conformity arrived. On 27 September Abraham Cheare and one of his close followers Edward Cock were the first to arrive. George Hughes and his lecturer, Thomas Martyn were escorted by “two files of musqueteers” to the Island on October 6th whilst Nicholas Sherwill and Hughes son Obadiah were held in the Golden Fleece Tavern until they too were escorted by “four musqueteers with matches lighted” to the Island on October 9th with strict instructions not to converse with Mr George Hughes. This bought the total number of prisoners held on the Island to 6. Edward Cock died in May 1666 which would have been around the time George Hughes, his son Obadiah, Thomas Martyn and Nicholas Sherwill were released on bond. Their congregations or relatives would have paid security of up to £2,000 each for their release and they would have not been allowed within 20 miles of Plymouth or their congregations.

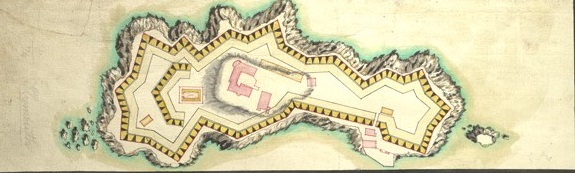

The prisoners were kept in isolation although they were allowed to receive food and clothing write letters to their family, friends and each other. There are reports that indicate they were allowed out of their cells or chambers under escort. On confinement Nicholas Sherwill was to “have a sentinel at his door and not to go out without a guard” although Abraham Cheare was confined to his cell throughout his incarceration. The cells were described by Cheare as underground “without light and mortally damp”. Mr Quicke who collected George Hughes from his cell on his release described the “keen air rusting the bars of the prison”. The only buildings on the Island at the time were 3 houses at the top of the Island used as a Governors House, Officers quarters, plus barracks, store and a powder house. There was also a small guardhouse where the current Governors House is located. No records exist of a separate prison being built and it seems likely that rooms in the existing buildings, probably in the basements were used. Some of the store rooms would have been barred and without windows anyway and there were probably a couple of cells to hold prisoners from the Garrison on the Island as well. With the small number of prisoners on the Island the maximum number of cells needed was only 6 and then for only 9 months so it seems reasonable that the Island would have been able to find that amount of space bearing in mind the buildings were designed for a garrison of 300.

Abraham Cheare, now the only prisoner on the Island was joined in 1667 by the last prisoner to be incarcerated Major-General John Lambert. He was the last commander of a Parliamentary Army who marched north to meet General Monck and prevent the Restoration but woke one morning alone as his Army had deserted. Arrested and thrown in the Tower of London he used what was then a common means of escape from the Tower. The Yeoman of the Guard or Beefeaters aren’t the fine upstanding men you now see at the Tower. Back in the day they were generally prone to bribery and given the choice between drinking and doing their duty generally opted for a booze up. Thus Major-General Lambert got his guards drunk and escaped by climbing down a knotted silk rope and was rowed down the Thames by barge. Unfortunately the rest of his plan wasn’t that well thought through and he was recaptured on Guernsey, tried, found guilty and transported to St Nicholas Island in 1667 making the prison population just two.

Both Cheare and Lambert would have heard a great deal of commotion on the Island during 1667. The Governor was warned the enemy, we were fighting the Dutch in the Second Anglo-Dutch War at the time, were intending to “burn and spoil the Western Coast”. In June a number of local ports raided and the Island was victualled for a month siege with cannons hauled onto its “exposed parts” although in the end Plymouth was not directly attacked.

The next year Abraham Cheare succumbed to his illness and died leaving Lambert as the last prisoner. He received a couple of visitors over the years including Charles II and the diarist Samuel Pepys. During his imprisonment he was allowed out of his cell under escort but was alone apart from his guards until he died on the Island in 1684 when the Island ceased its role as a prison and became solely a fort again. Charles only outlived his last prisoner by a few months dying the following year in February 1685.

Finally there was local rumour mentioned to me by more than one person that there was an oubliette used as part of the prison. An oubliette is a cell entered by a trap door, once prisoners are incarcerated they are generally left to die. This was said to be where the existing Artillery tower is, however it was still being used as a gun emplacement when the Island was a prison as we were intermittently at war with the Dutch. The confusion seems to stem from an entrance at the top of the tower. However the internal brickwork of the tower dates from the 18th century when the tower seems to have been adapted as a water cistern which would account for the trap door. Additionally they were not widely used anywhere and especially not in England. Their use was popularised and exaggerated by 19th Century novels but most rooms originally thought of as oubliettes in Britain have turned out to be storerooms or cisterns. Personally I think it seems highly unlikely that an oubliette ever existed as part of the Island prison but without more detail about how the prisoners were detained on the Island it is impossible to be absolutely sure.

The years as a Prison seem to be part of a wider display of power to secure the restoration of the Monarchy. Although only a few prisoners were ever kept on the Island they were all high profile and showed the power of Charles II whilst sending a warning to rebellious Plymouth about the consequences of defying Royal authority. Next week the Naval Dockyard is moved from the Cattewater to Devonport involving changes to the Islands defences.