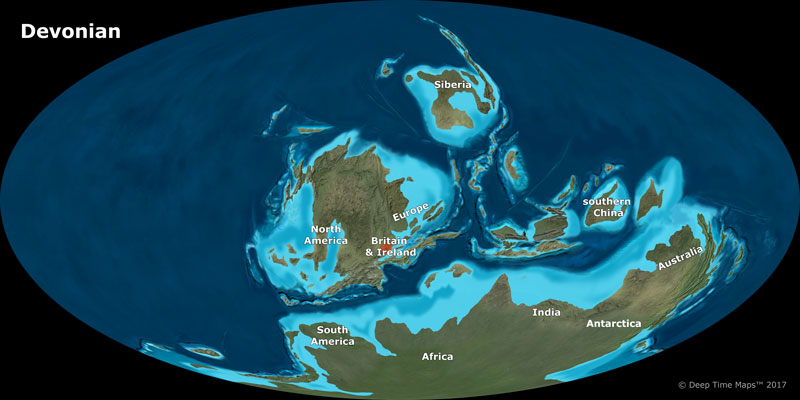

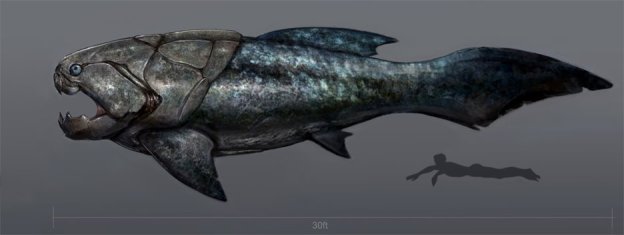

Our Island’s story starts some 4 billion years after the Earth was formed and about 350 million years ago. The Earth was in the Devonian Age or Age of the Fishes and it was a time of high sea levels with two supercontinents, Gondwana and Euramerica in one large ocean. The area that was to form South-West England was on the coast of Euramerica.

As the numerous marine organisms that lived off the coast died their remains fell to the sea bed. Here they compacted under the weight of the water and gradually fossilised. This process formed the Devonian limestone that dominates the geology of the Devon coast and is part of the rock formation of Drake’s Island.

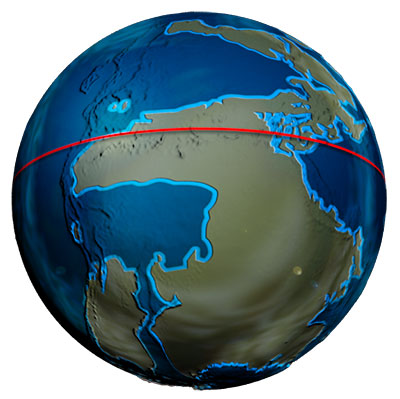

A little later, around 335 million years ago continental drift meant the two landmasses collided forming one landmass, Pangea. The land that would become Great Britain lay near what was then the equator at the centre of this super continent. It was an arid area, think of modern day Ethiopia and on the edge of large volcanic mountain range caused as the two landmasses pushed against each other.

The last volcanic activity in the area probably occurred around 290 million years ago. The lava and volcanic ash from these eruptions formed the other geological elements on the Island, the fossilised lava and Tuff or Tufa which is compressed fossilised volcanic ash. The type of lava was rhyolite which means it oozed out of the volcanic vents rather than the result of sudden violent eruptions. In fact fossilised rhyolite lava flows can still be seen in Cawsand Bay across from Drake’s Island. The intervening few hundred million years saw shifting tectonic plates and continental drift, Ice ages and post glacial floods that have shaped how the continents look today.

Our earliest human ancestors, Homo Antecessor and first arrived in what we know as the UK around 850,000 years ago in Norfolk. Fossilised remains of a later ancestor, Homo Heidlebergenis from 500,000 years ago have been found in Sussex. Similar tools and axes that used have been found near Torquay so it is possible that they could have been in the Island’s vicinity. These early humans would have left as Ice Ages advanced and returned as they receded so there would have been no continual occupation. Neanderthal remains from 230,000 years ago have been found in Wales so it is possible they could have been in Devon as well but there is no evidence. The earliest direct evidence of us, modern man, near to the Island is from Kents Cavern near Torquay and is a jawbone dated from 40,000 years ago. These were mobile groups so could quite possibly have been in the area that would become Drake’s Island especially as it still wasn’t an Island at this stage.

However 25,000 years ago the last Ice Age started and humans again left Great Britain. Humans returned about 11,000 years ago and we have occupied Great Britain continuously ever since. Numerically human numbers are difficult to assess but the population of the UK around 2,000 years ago has been estimated at 150-250,000.

Finally after the last Ice Age finished around 10,000 Drake’s Island began to take its current shape. Rising sea levels cut off Europe from Great Britain around 8,000 years ago. The land bridge between Drake’s Island and Mount Edgcumbe in Cornwall flooded permanently around 3,000 years ago creating the Island. The Island would have looked very different in terms of flora. The majority of the trees and other flora were transplanted from the mainland using offcuts provided by the City Council to the Adventure Centre in the 1970’s. Until then the Island would have looked bare. The only addition being earth transported to the Island after 1550 for defensive works to protect the guns. For a comparison look at little Drake’s Island next to the main Island for an idea of how the Island would have looked with only defensive works until the 1970’s.

The formation of the Island has impacted how it has been used. Its location within the Sound and the difficulty in attacking the Island meant it was a safe refuge during the Western or Prayer Book rebellion in 1549. The shallow passage on the Southern side facing Cornwall together with its narrow passage on the Northern side facing the Hoe gave the Island its strategic importance as enemy ships were naturally channelled into the range of the guns on the Island once gunpowder and artillery came into use during Tudor times. The first fort on the Island dated from 1550 and artillery could fire on any ships trying to attack Plymouth. The Limestone, Lava and Tuff are all soft rock allowing the tunnel complexes and underground chambers to be dug out during the construction of the Palmerston Forts in the 1860’s and the strategic position was again key as a defence for Devonport from a seaborne threat in both World War 1 and 2. Next week an investigation of the first building on the Island a votive chapel built by the Valletort Family and named St Michael’s Chapel.