Both Ken Corish and Martin Dunning started work on the Island in 1979 as instructors, Ken as an Assistant Marine Biologist and Martin as a climbing instructor. There were two ways of getting a job on the Island, replying to an advert or through someone you knew. Ken responded to an advert and describes his interview experience “An early morning start at Mill Bay Docks and out of the sea mist appeared a boat piloted by Anya, a solitary female skipper. The early morning boat-run on the island’s main vessel, an eighteen footer powered by a six cylinder Gardiner diesel engine grandly titled the “Sir Egbert Cadbury” but known affectionately by all as “Choccy”. Out of the morning mist loomed the unmistakeable outline of the Island, much bigger up close than when viewed from the mainland. Up to a dilapidated concrete and timber jetty and along the sprawling concrete of the jetty’s length to meet the Lead Marine Biology Instructor Nigel Shillabeer. Introductions and then up to the main Barrack Block building where the Marine Biology Room was housed; a classroom layout with a blackboard, bookshelves and a sea water aquarium in need of some loving care. We ran through a quick interview and an identification walk around the immediate foreshore and that was it; I was in. I began the next weekend”. Martin’s interview was similarly brief “I was 22 when I went to work on Drake’s Island in April 1979. A friend of mine was head of climbing; they were short of instructors and Pete phoned to see if I wanted a job for the summer. At the interview we drank coffee and talked about climbing for a couple of hours and Pete said I’d be starting the following Monday. No HR, CVs, or references”. Over the next couple of weeks I’ll be sharing their memories starting this week with Ken.

“Drakes Island Adventure Centre was managed by the Mayflower Trust. Each week from early March through the season to Late September, the centre would receive groups from the City and beyond. Early groups would be older students, usually dockyard apprentices from Plymouth, Portsmouth and Chatham for personal development and expeditionary activities both on and off the Island. But the main bread and butter, as the season progressed and weather improved, was schools”.

“Residential courses would arrive on the Island from as far afield as South East, the Midlands and the North West, arriving on a Sunday and leaving on the following Saturday morning. Non-residential courses would usually come from local Plymouth schools and attend each day as a group with their staff. They boarded at Phoenix Wharf on the Barbican and were ferried across by a large tourist vessel plying its trade at that time; the “Lady Elizabeth” run by the redoubtable Ernie; a man with such a strong Plymouth accent not even locals understood what he was saying half the time”.

A week’s course at the centre would include:

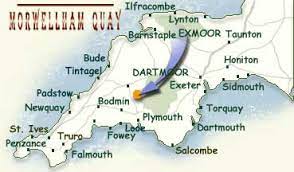

Canoeing; the island owned 20 plus canoes and kayaks and actually made many of these themselves over the winter in fibreglass canoe workshops based down in one of the old gunnery rooms or casemates. Canoe groups would do Island circuits or across the Sound to the Hoe. Older groups would go on an expedition right up to Morwellham Quay….a long haul that required an overnight camp.

Sailing; 2, 18 foot Musketeer day boats with a fleet of about 10 Wayfarer dinghies alongside a beautiful Drascombe Lugger. All of these were accompanied by a safety boat, sometimes a Dory with an outboard or a beautiful 12 foot Plymouth Pilot called Mallah (Hallam backwards after its benefactor). I fell in love with this boat as it had an inboard engine started with “starter cigarettes” and a variable pitch propellor. Small as it was, it could be held in even the roughest of seas with its versatile controls; an excellent safety boat but awful if it got a rope fouled around the propellor. The shaft only rotated one way so each time it was fouled I (as the Island’s lead diver) would have to drop over the back and cut it off with a knife underwater. No fun at 6 o’clock on an April morning before the day began.

Marine Biology; whilst this sounds the least exciting activity we designed it to be a fun learning experience. Each day began in the classroom with some prep for a seashore rock pooling competition followed by snorkelling practice in the calm waters around the beach and jetty. Part of my first role was to purchase a set of wet suit shorties; self inflating like jackets; masks; fins and snorkels from Sandford and Down Diving supply store in West Hoe. These were stored in a small dive store just below the entrance to the staff accommodation in Island House. For many children, they had never experienced what the ocean on their doorstep looked like once you immersed yourself in it with the right equipment; the Island was perfect for this. Clear water washed by tides in the Sound with rocky reefs and eelgrass beds. During one of the seasons we were accompanied each day by a friendly grey seal (Sammy, what else?) who would swim up behind unsuspecting kids and nibble on their fins to play with them. On days where poor weather meant snorkelling could not take place, we took groups over to the old marine aquarium based at the Marine Biological Association on Plymouth Hoe. In later seasons we ran week long diving and A Level specialist course in Marine Biology for secondary schools. We even established the Drakes Island Sub-Aqua Club as a branch of the BSAC and began to train divers.

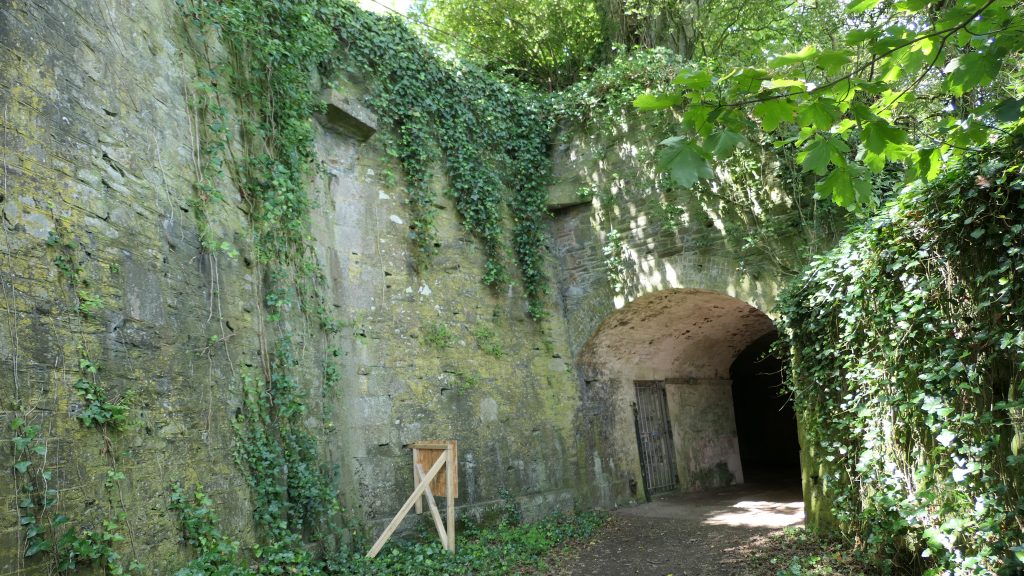

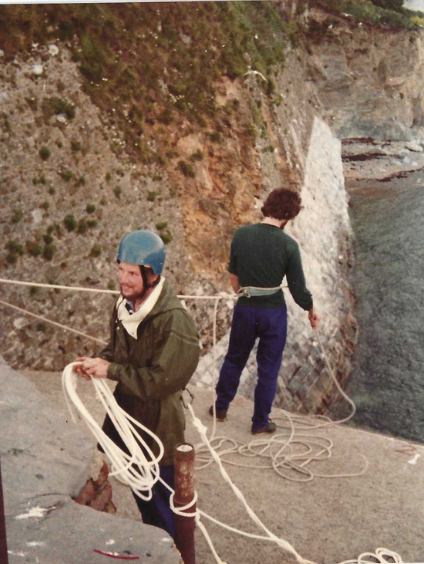

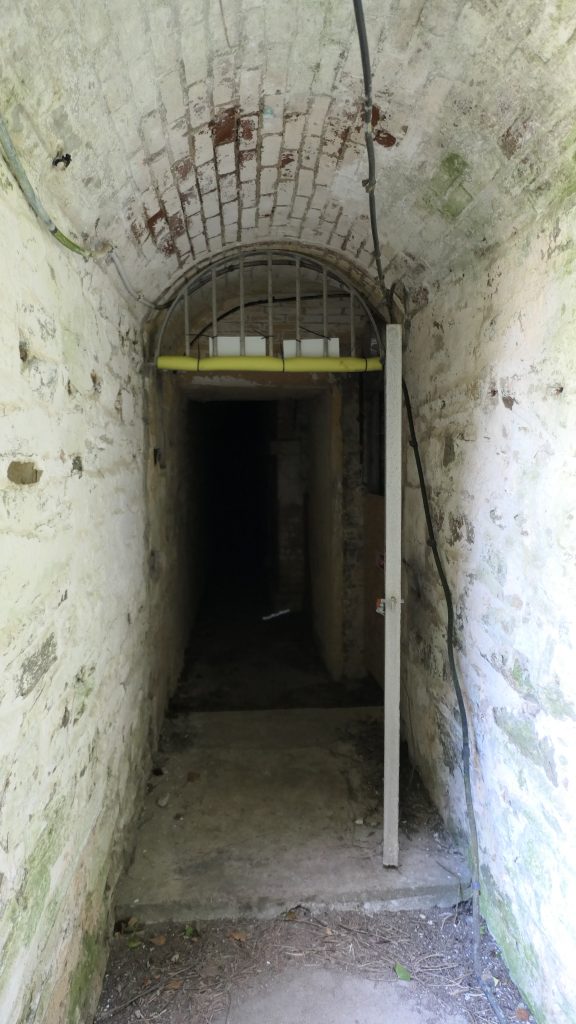

Climbing; this mainly happened on the Island for non-residential groups where we built a climbing wall at the far end of the covered walkway. Abseiling would also happen; contact abseiling and return climb on the buttress at the back of the Island and an amazing 70ft free abseil from the crane hoist overlooking the boathouse on the landward side. Simpler challenges for students were set up on the old torpedo chute between the casemates. This was a steep ramp where wire-guided torpedos gained access to the the seaward foreshore during the Wars. Some older groups were taken by minibus out to the Dewerstone to climb”.

Caving; this was principally off Island using the caving systems out at Pridhamsleigh and Baker’s Pit near Buckfastleigh or at Radford Caves closer to home in Plymouth. For days when weather restricted travel, we built a caving circuit in amongst the Island’s own tunnels with crawls, squeezes and climbs.

All of these activities were supplemented with evening activities that included: Island traverse; groups of children roped together and blindfolded and then led over an obstacle course!! Concert nights in a little theatre we built in one of the casemates where staff and children would “do a turn” for a rowdy yet appreciative audience. Film nights; the Island had its own projector, screen and sound system but only two films. A Tom and Jerry cartoon and “The Wild Geese”… I came to despise both of those films. Boat trips around the Sound as dusk fell and to watch the amazing bioluminescence churned up in the wake. Disco party night: usually held on the last night in one of the large magazine stores accessed half way down the covered walkway. The room was suitably painted, and lit with a large DJ system and record collection. Reminiscent of the Cavern in Liverpool, the condensation would literally be dripping off the walls at the end of the evening,

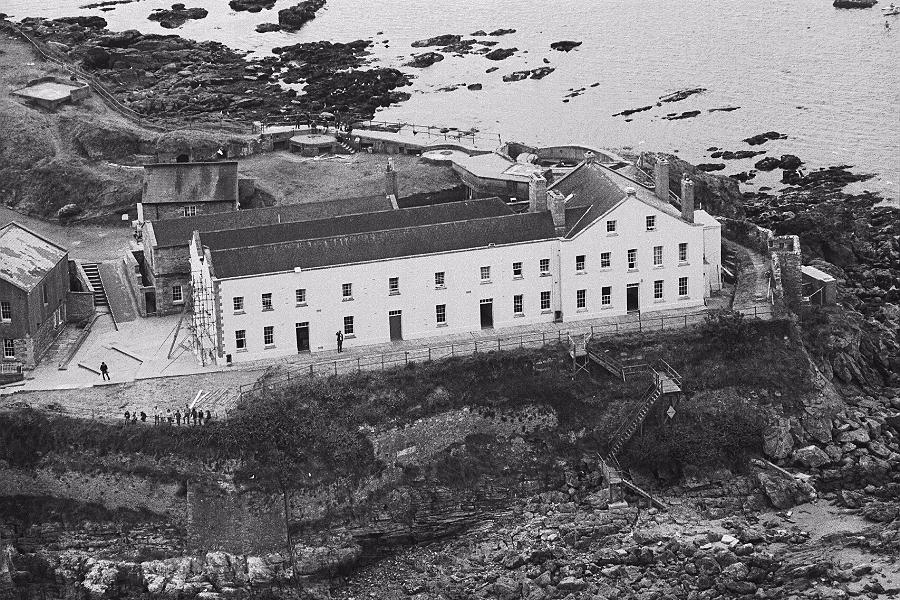

Feeding all of these people was huge task; the kitchens were at the western end of the Barrack Block and run by two chefs and two Kitchen Porters. Breakfast and dinner took place in the dining rooms at separate sittings with packed lunches for the rest of the day. At any one point during the season there could be over 300 people on the Island including 30 plus staff and instructors; residential visitors and non-residential visitors. Each day would see several visits too from local day trippers during the tourist season. The Lady Elizabeth would run five round-trips each day from Mayflower Steps to the Island to Cremyll and back to the Barbican. The Island had its own guided tours for these tourists run by local experts such as the inimitable Stanley Goodman who had a long history with the Island. It even had its own souvenir shop and cafe. It sold refreshments and souvenirs: badges, pottery; Drakes Island Fudge and guidebooks. The usually isolated sandy beaches on the landward side of the island (next to Little Eye, the smaller island alongside to the main one) would be full of tourists, gaining access down what was always a rickety staircase in front of the main Barrack Block. One of our unofficial jobs was to chivvy late tourists from the beaches who were in danger of missing the last boat or in some cases stranded on Little Eye when the tide came in. The Island at the time was open access and very popular with the people of Plymouth as well as tourists”.

During my first season there in 1979: The boathouse was constructed and a new slipway refurbished alongside it. The jetty was reconstructed with a steel infrastructure and grating to make landing safer for the larger vessels rather than the original timber. The accommodation in the barrack block was refurbished and new bedding purchased. We adapted one of the casemates to act as a base for unemployed teenagers who were part of the Youth Opportunities Scheme (YOPS) so they could work on the island’s maintenance tasks; landscaping; building maintenance; canoe building; boat repairs. We began work on a converting one of the casemates into a staff club; repainted in midnight blue and white with blue carpeting; wood clad walls and a purpose built bar. It had a grand opening with local dignitaries but immediately fell into disrepair and lack of use through continual flooding and damp.

As the season closed in 1979, I returned home but was then employed as permanent member of staff and Senior Instructor in Spring 1980 until I left in Autumn 1982. As Senior Instructor we took responsibility for the administration of courses and not only became Course Directors but also for attracting new schools to the charity. We ran advertising campaigns with visits and talks to local schools and began to build a strong local engagement.

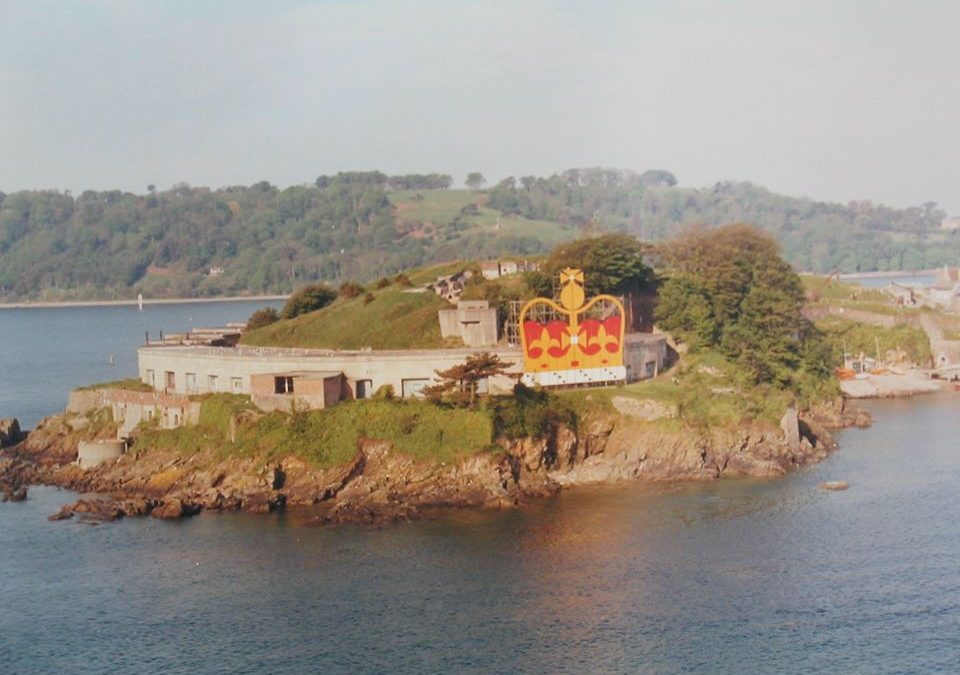

Each season seemed to improve on the last: more people; busier than ever; more connections. During that time we saw the building of a huge crown above the casemates to celebrate the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. Watched Royal Marines and Sappers excavate and reposition the huge canon at the top of the Island, tackling the heavy lifting with helicopters. Watched the final journey of the Ark Royal as it left the Hamoaze. Watched ships including the Atlantic Conveyor being prepared for the Falklands War. Consecrated Drake’s Island Chapel in one of the casemates with the assistance of Rev. Donald Peyton-Jones, a great Island friend and who ran the Missions for Seamen. Watched the annual Hoe Fireworks from the best vantage point in Plymouth. Explored the enigmatic Oubliette. (No one was sure whether it was truly a prison cell but it had been there since Napoleonic times; good to frighten the kids with though). Cleaned out the western septic tank with our bare hands, a job I will never forget as long as I live. Reroofed the wet weather store opposite Island House near the main entrance to the Island. Dug and searched for the fabled “third layer” of tunnels. Moved and cleaned the Drake’s Island model for display in the tourist tunnels. Buried my poor old dog who died of parvo virus under the trees at the top of the Island.

My new role as permanent staff now allowed me to experience Drake’s Island winters. As the last of the courses finished and instructors were laid off, a crew of about 5 of us stayed on the Island for maintenance work. This was a lot harder than I had anticipated; bad weather would strand us for days. Boats were kept on running moorings about 100 metres away from the jetty and meant rowing out to them in a small dinghy. Even with all the best wet weather gear it was often an impossible journey to make…and dangerous too. This just meant hunkering down until the weather had blown through. On really bad nights with a high tide and large westerly swell, waves could break green over the whole island flooding our accommodation with seawater, sand and debris. There were occasions when there were only two of us on at a time and one of us had to keep running boats to get crew ashore. This left the other alone for short periods of time to check on tunnels, workshops, accommodation…. not for the faint-hearted moving through those tunnels at night alone, switching off power supplies and checking padlocks. The final winter was the hardest. Over the period of a few months our water and electricity supply lines were damaged (allegedly by a buoy laying ship operating in the deep-water channel “Pintail”) which meant no fresh water nor electricity for several months. We were supplied with a freshwater bowser positioned at the end of the jetty where water was hand transported in jerry cans and a generator was delivered which we housed in the boathouse but had to run continuously, very often needing refuelling at all hours of the night. As the Island diver, I was asked to check the water line to see if we could repair it but it proved to be a dangerous deep dive in a fast-flowing part of the deep water channel (up to 40m) and had to be abandoned part way through. The visibility was good and seeing that drop off into the darkness below was an eerie and frightening feeling; hooked on to a water pipe, the other end going God knows where. It was in the summer of 1982 that I had decided to leave as I was joining a post grad teaching course in the September; the conditions; the weather; the spartan life and the cabin fever had proved too much for me. It was the polar opposite of what the Island was like during the summer season. Lively. Busy. Fun. Varied. Exciting. It was a hard wrench as living on an island was quite a special thing, but not without its own difficulties. So we moved; setup home in Plymouth and I went into teaching.

I have been married now to my wife Donna for nearly forty years and I met her when she worked as Kitchen Assistant on Drakes Island in 1981. We both met, got engaged and lived in my room in Island House overlooking Plymouth Sound for our first two years together. When we both left, we stayed in Plymouth for the rest of our lives. We have four beautiful daughters, all Plymouth Maids, and eight wonderful grandchildren. We have a lot to thank Drake’s Island for and it’s not lost on us that as we gaze out at the wonderful place where we first began our journey, we will someday revisit to say thank you to an exceptional experience that means so much more to us than just another part of the City.

Just to say a huge thanks to Ken for sharing his memories of the Island, It is fantastic that we can preserve the social history of the Island as part of the heritage for future generations and I hope you have enjoyed Ken’s recollections as much as I have – Bob.

Brilliant to hear from Ken. Lovely to hear you and Donna are still in Plymouth.

I was a canoeing instructor in 1982/3. Living and working on Drakes Island was such a happy time.

I’m delighted to see that the island may at last have some life breathed back into it. A joyous place.

Great to hear you story Ken. I’ve been back to the island once since I left in 1980. I was doing an Environmental Impact Assessment for a previous developer.

It led to a career in Marine Biology all based in Brixham, happily retired now. Always fond memories of the island.

I first played on the island as a child in the 1960’s. My Mum’s youth club ran activities there and she ran a shop for visitors.

I went to Drake’s Island around 1978, 1979, I can’t remember exactly, I’m 59 now. But I remember being a troublesome youth and they sent me there as an alternative to punishment after at least my second appearance at juvenile court in Chichester. I remember being very afraid to go, I can remember waiting at the dock for the boat to pick me up, I can remember the frothing grey ocean, the cry of the omnipresent seagull the fear of the unknown; thus far I hadn’t been more than a few miles from my own front door.

But it turned out to be a magical experience for me, abseiling, canoeing, sailing etc; the cold, the wind, the rain, the thrill of the early morning. I remember we canoed for a whole day, it was like a grand adventure to me. It was the first time I connected with nature, felt the joys of a simple meal after an exhausting day. There was a lot of bullying though; it was like lord of the flies after lights-out in those old barrack rooms. But I loved it, there was a library I remember vaguely, I use to retreat there and read during our free times, it was my favourite place. Drake’s Island had the impact on me that those that sent me there hoped it would!

I joined the army in 1979 at 16 1/2 as as a boy soldier, which you could do then, and such experiences became everyday to me. But Drake’s Island holds a special place in my heart. I’ve lived in the US for 30 years now, but will go back one day and sit quietly and meditate there.

Thank you for sharing your experiences as an instructor, it was a pleasure to read!

Hi Sean, thanks for taking the time to comment and also for sharing your memories of the Island every little detail helps build a picture of the Island’s history. If you are back in the UK at any time the only way to currently visit the Island is by a conducted guided tour going to and from the Barbican and lasting 2 to 2 1/2 hours. At the minute there is no opportunity to wander off and explore on your own but this may change into the future. If you want to book it is all online via drakes-island.com and there should be a link to the tickets. Current cost is around £24 including the return ferry ticket from the Barbican.

Lovely to read this and it certainly brought back memories. Ernie the skipper of the Lady Elizabeth was a very kind man.

One of my fondest memories was when for reason I ve forgotten now, the Admiral of the Ports barge came and took Martin and I off to Millbay. The matelots did a synchronised salute with the boat hooks. Very smart.

I remember the Ken / Donna romance starting , how lovely to get an update.

Martin and I were a couple (1979?) but I married the Head of Sailing (1980?) Chris Rolle and we now live in Norfolk having enjoyed racing Flying 15’s in the Lakes previously.

Yes I loved my time on Drakes Island and remember those times and people with great affection